“For as long as humans have been writing,” writes Michael Finkel, “we have been writing about hermits.” He thinks that we have a “primal fascination” with them (p. 37). This fascination, I believe, stems from the tendency to idealize those who turn their backs on society and seek a new world, an impulse many people might share without intending to act on it.

Today’s hermits are men (mostly) who have decided that wilderness offers them more than society does. They assume that solitude is better than the social life they have known. They take it for granted that they can survive in the wilderness. Even men who have grown up in the woods long for primitive cabins. Patrick Hutchinson, for example, bought one south of Seattle for $7,500, “a wooden box with a roof and a door,” that is, as he describes it, “perfect.”

Above: The Temptation of St. Anthony in the Desert, from the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald (1512-16). He is the bearded, reclining figure in monastic attire.

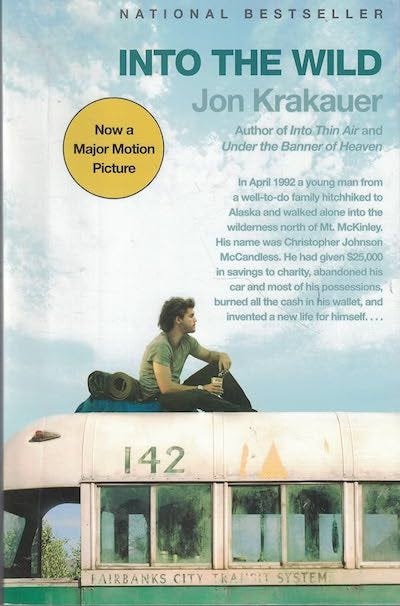

The hermit’s solitude is paradoxical. It takes him into himself but also out of himself. Along with peace and isolation, he finds that he must struggle to survive. Accounts of four modern hermits follow. They show that today’s hermit, like his ancient predecessors, cannot survive entirely on his own. Only one of the men I write about was truly isolated, and things do not turn out well for him. He is Christopher McCandless, the hero of Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild (1997), which became a 2007 film that was written, directed, and produced by Sean Penn. Also well-known is the story of Christopher Knight, told by Michael Finkel in The Stranger in the Woods (2017), another best-seller.

Two hermits tell their own stories: Dick Proenneke, One Man’s Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey (1973); and Ken Smith, The Way of the Hermit: My Incredible 40 Years Living in the Wilderness (2023). These modest and thoughtful books, half a century apart, offer strikingly similar views of the eremitic life and how its risks can be managed.

Early hermits

The Greek erēmos means “wilderness.” It is not surprising that each of the world’s great religions has an eremitic tradition. The hermit acquires wisdom in the wild, partly through the magic—or at least the strangeness—of the great outdoors. The archetypal hermit in Western culture is John the Baptist. The prophet Isaiah referred to him as “a voice calling in the wilderness.” John called for obedience and action: “Prepare the way for the Lord, make straight paths for him” (Matt 3:3; Mark 1:3; John 1:23; Luke 3:4).

John’s significance is nowhere shown better than in Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16), an immense work located in Colmar, France. The altarpiece comprises two sets of folding panels that could be arranged to reveal narratives related to Church feast days and seasons. For Lent and Advent what is known as the “closed” position (covering glorious sculpture) was used; the panels show the Baptist, mouth open, and next to him text in red (“He must increase, but I must decrease,” John 3:30-35). John the Baptist was beheaded long before the death of Christ; the John quoted here is, of course, the evangelist, who is seen on the left supporting Mary, the mother of Jesus.

The altarpiece’s Crucifixion panel alone is 10’ wide and over 8’ high; with the two side panels, not shown here, the altarpiece is over 15’ wide.

Like many others, Christ sought out John and was baptized by him. Christ was then “led up by the spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil” (Matt. 4:1). Some details are provided by Matthew and Luke, who describe how Satan tested the Lord’s need for food, security, and power. Having, like John, passed his test, Christ left the desert to begin his public ministry (Matt. 3:3-10), ready for a future that, like John’s, ended in violent death. Martyred or not, every ancient hermit died to his self, which he submerged in his prophetic role.

Of the many monks who followed John and Jesus, the most famous is St. Anthony, a hermit in the Egyptian desert (c. 251-356). His life, written by Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria (c. 296-373), became a model for monastic devotion. Just as Anthony would have his desert followers, he was himself the first to follow a hermit. After he had gone to the desert. Anthony learned that Paul of Thebes had gone before him. Anthony found Paul’s cave and the men became friends. This moment too is captured on a panel from the Isenheim altarpiece, with St. Paul the Hermit on the right.

The life written by Athanasius started a hagiographic tradition, and with it eremitism escaped the wild and took root in the classroom. The Life calls on readers to enter into rivalry with the monks of Egypt, with Anthony’s piety especially, and to “bring yourselves to imitate him,” meaning to live a life of sacrifice. Instead of immersing themselves in nature, monks read about those who did—much like those of us who read about modern hermits without needing to imitate them.

Anthony’s message, like John’s, was that salvation had to be earned. Anthony left wealth and privilege behind. In the wilderness, he was, like John and Christ, tempted, besieged, a phenomenon unforgettably captured by Grünewald. Anthony found himself overwhelmed by visitors as well as demons. To get away from the former, he sought less hospitable places where he hoped to live alone. Yet admirers continued to find him and bring him food. Ashamed of this dependence, Anthony began to till the soil, creating a model for modern hermits who, like him, want to earn their bread. Independence is the key to the eremitic life.

Christopher Brooke has described the enthusiasm of early hermit. He points out that enormous monasteries like Cluny (in Burgundy) were surrounded by hermitages “for those who felt the call to live in solitude.” Their model was the Desert Fathers, Anthony among them, and those who looked “for a more lonely and heroic approach to the divine presence” than the monastery offered (p. 75). Modern hermits fit this pattern, not in approach the divine presence in a Christian sense, of course, but in their search for a purer and, it is not too much to say, a holier way of life.

Modern hermits

Like his ancient forebearers, the modern hermit sets out to prove himself. He seeks destinations that offer minimal protection and limited resources. Alaska is the choice of McCandless and Proenneke. Before he settled in the highlands of Scotland, Smith traversed Canada and Alaska. Knight went to northern Maine. These places are sparsely populated, with difficult terrain, punishing cold, and heavy snow, sites that are prized for their environmental integrity and purity. Where we find the modern hermit in the wild, we see the environmentalist in his chosen environment, which is both magical and threatening.

The modern hermit should be distinguished from the survivalist, who stays at home but prepares for emergencies of all kinds, a movement discussed in EJ Snyder’s Emergency Home Preparedness (2024). Although the wilderness offers an experience outside the social routines that ordinarily carve up life, the wild imposes its own rules. Nature follows the laws of day and night and the unpredictable demands of weather. A man in the wilderness is an intrusion of culture into nature. Nature is not concerned with his needs, any more than nature worries if birds have enough to eat. It is in this contest between man and nature that the modern hermit’s significance lies.

The hermit narrates his own adventure in two of these books. One of the most highly regarded works about the wilderness is Richard Proenneke’s One Man’s Wilderness, which was made into a television film in 2004 (he lived 1916-2003). He was extraordinarily accomplished. In the foreword, Nick Offerman describes him as “a notoriously talented diesel mechanic, gifted woodworker, chemist, fisher, navigator, gardener, and journalist” (p. vii). Set a man with these talents loose in the wilderness, give him the right tools, and watch something wonderful happen—although at a carefully measured pace.

After visiting the Twin Lakes area of Alaska, south and west of Anchorage, Proenneke built his cabin there in Spring 1967. He returned to his cabin every year for 30 years, although in his latter years he did not winter there. Since 2007 his cabin has been on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the preface to the book, Sam Keith notes that he worked with Proenneke in Alaska, on the Kodiak Naval base, in 1952, when Proenneke was 36 years old and was employed as a carpenter. At 50 Proenneke retired and took up life in the woods. He and Keith had explored Alaska together during their Navy years, and having known Proenneke for so many years, Keith compiled the book we know as One Man’s Wilderness from his friend’s drafts.

Camped on a lake, Proenneke was always in motion, and so is the world around him. “Wind and fire,” he wrote after a canoe trip made against and then with the wind, “help you one minute and kill you the next” (p. 87). That mix of assistance and danger seems to be the magic of the wild. Proenneke’s actions rested on a firm foundation of good sense and knowledge. He wondered, on a given day, how far below zero it was (-45? -54?). It was all the same to him as he bundled up and headed out to track game or gather wood.

Proenneke saw many others enter the wild to hunt and fish. A man with vast experience of the wilderness and its animal life, he disdained most hunters and their guides. He found game they left behind and dressed and cooked it. He regarded campers as careless, ignorant, and wasteful (e.g., pp. 133-35).

Apart from his extraordinary range of wilderness skills, Proenneke was regularly supplied by a pilot friend, who on one occasion arrives unannounced, with 50 pounds of sugar, four ten-pound sacks of flour, dried apples, raisins, and pitted dates. On another visit the pilot comes into the cabin and shares a pot of beans and onions that has been over the fire for several hours. Proenneke is amused that the pilot envies the purity and serenity of the the cabin. The visitor is a Christian fundamentalist and must leave to spread the Word (p. 171).

Proenneke subscribes to a creed of his own. He offers thoughtful philosophy on the endlessly expanding dependence of people on manufactured things that save time and make life easier. Ease and lots of time are not things he prizes (p. 245). He hints that we should ask ourselves if we need all the things we have around us. He definitely needed the things around him, for his survival depended on them.

Fifty years after the publication of Proenneke’s book, the Englishman Ken Smith published The Way of the Hermit (2023). Unencumbered by Proenneke’s caution, Smith seems determined to persuade the reader to embrace life-threatening danger as a way to discover the meaning of existence.

Smith survived a near-fatal beating when he was teen, after which he had to learn again to write and speak; he underwent a long recovery period (pp. 47-49). Before settling in Scotland, he hiked in Canada and Alaska (pp. 55-61). Smith eventually located himself in the highlands, about 100 miles due north of Glasgow, where he stayed for 40 years. Smith’s motto is “the hermit lives to fight on” (p. 12), but he knows that he isn’t strictly a hermit. He thinks of himself as a homeless vagrant (p. 14).

His first dwelling is a “boothy,” a kind of shed that served as a year-round shelter home for farmers or estate workers such as sheep herders—a roof, a sleeping platform, a place to cook, maybe a fireplace, basic but, Smith says, “absolutely palatial” when compared to a tarp or a park bench (p. 95). “Boothies” were meant to be used by anybody who happened by. Smith sometimes has to share one with other hikers, some of whom are considerate of the public nature of the shelter. Others come with drugs, including heroin (pp. 105-6). They burn the wood that had been gathered by other hikers and do not replace it, even burning furniture and floorboards (pp. 105-7).

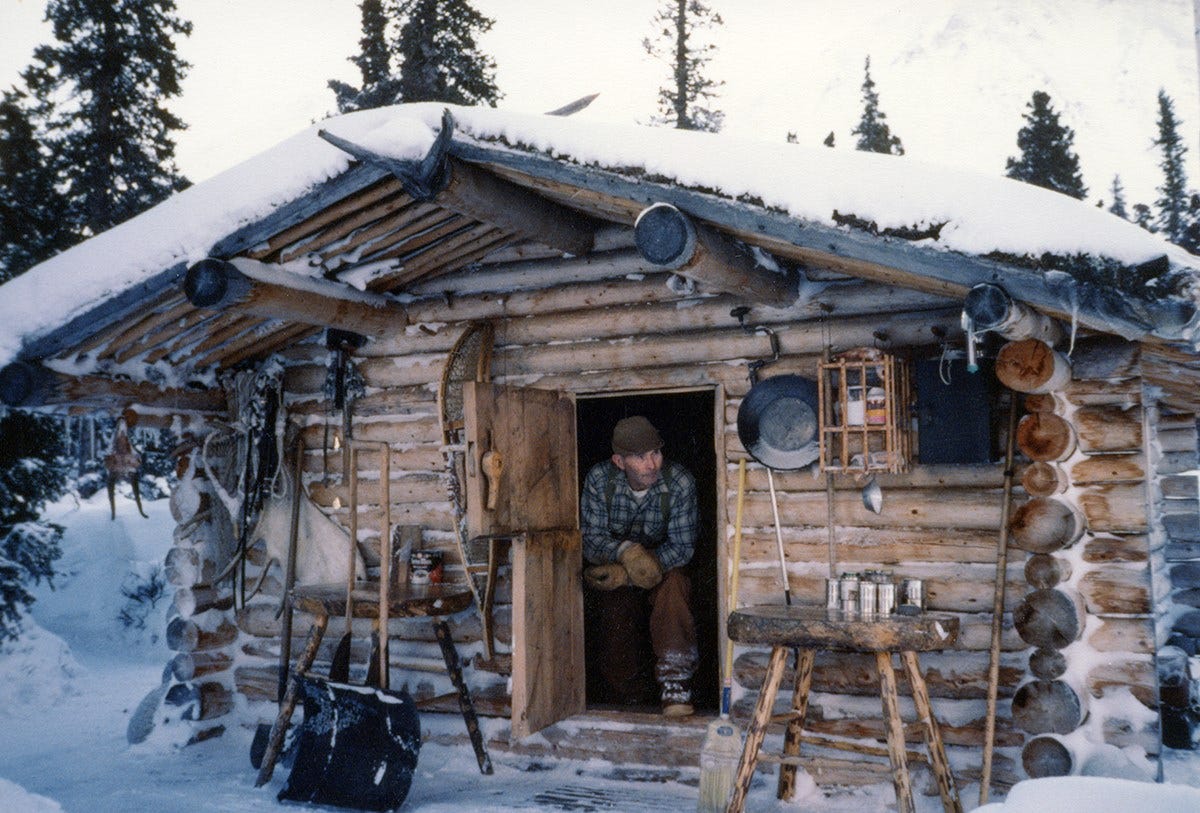

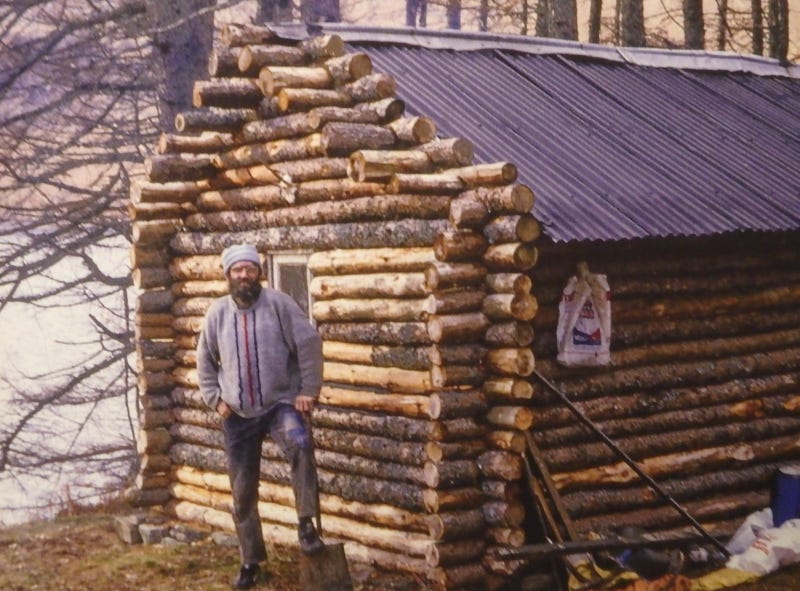

When Smith comes to Loch Treig, he decides to build a cabin. He has to get permission from the owner of the 57,000-acre estate on which his chosen site is located (p. 117). It takes a while, but permission is granted. At this point he recalls Proenneke’s time in Alaska and his work building a “traditional Canadian log cabin” (pp. 129-30). It would take Smith two years to build his own, but the results would be what he had been longing for. As you can see from these pictures, their cabins, which were built single-handedly, but with the right tools, were not modest.

Proenneke’s cabin

Smith’s cabin

Like Proenneke, Smith learned to live “off the grid.” But he was not cut off from human contact. He worked as a “ghillie,” or guide to hunters and fishers, as “help” to the upper classes “in their outdoor pursuits.” He busied himself that way until he retired. (pp. 150-51).

Proenneke was pragmatic. Smith was not. As if living in isolation weren’t scary enough, Smith had paranormal experiences. He fled one dwelling because he believed it was haunted; he was not the only one to think so (p. 15, p. 103). Aware of how vulnerable he can be, Smith makes a supply run on a day when a huge snowstorm moves in. Fighting his way home, a walk that takes more than four hours, he becomes confused and, suffering an illusion, mistakes a herd of stags for people and follows them. Then he retraces his steps and becomes disoriented. He reminds us that hikers in such situations sometimes die just a few feet from their refuge (pp. 124-26).

If you are marching through piles of snow in frigid temperatures, Smith writes, you must never, ever stop, for if you do we will sleep, and if you sleep, you will die (p. 230). This phenomenon is well-known. I noticed a reference to it in Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel, The Magic Mountain. Mann discusses “oblivious self-deception” and compares it to how “the temptation to wander in circles overcomes someone who is lost or [how] sleep ensnares someone freezing to death” (p. 635). In a novel called Light of the World (2013), James Lee Burke describes a part of Kansas where the term “cabin fever” originated; farm women went crazy in the severe winters and killed themselves, “and a rancher had to tie a rope from the porch to the barn to find his way back to the house during a whiteout” (p. 15).

Like Proenneke, Smith was wise to the wilderness (pp. 135-37). Smith knows, for example, that bees are more likely to kill the wanderer than bears (p. 68). Never overestimating his readers, Smith offers advice on making tea (pp. 244-45). A man who has walked up to 18 miles, one way, for supplies, then turned around and walked home, he has little time for unprepared hikers who show up at his cabin with romantic ideas, seeking to spend time with a man they seem to see as holy (p. 237).

Smith has a gift for an apt turn of phrase. He writes that, when hiking in British Columbia and Alaska, he allowed himself to be “swallowed by the landscape” (p. 79), an ominous image to which I will return. Even though his experiences brought him close to death more than once, Smith exhorts his readers to take up their own adventures. Prove to yourself that you can overcome adversity, he says, “and I’ll tell you now, as I sit here as an old man, that is what you will look back on with the greatest feelings of pride. That is the way of the hermit” (p. 163).

The books by Smith and Proenneke contrast with those written by authors who interpret the wilderness experience of other men. Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild (1997) is about Christopher Johnson McCandless, a young man who searched for a new life in Alaska and died. Twenty years after Krakauer’s book, Finkel published Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit (2017). The book tells the story of Christopher Knight, who disappeared into the Maine woods when he was 20. He stayed in the wild for 27 years and lived to tell about it, surviving on food he pilfered from cabins. His isolation began in 1986, the year Chernobyl Reactor No. 4 exploded , and ended in 2013 (p. 17). He was tried and sentenced to seven month in jail, where Finkel interviewed him.

Knight chose to live in a secluded wood that offered access to a cabin used by campers and that contained a regularly restocked supply of food that he could easily plunder. This went on for years, but his thefts did not rouse the kind of animosity one might expect. People chose to leave him alone, admiring his eccentricity, respecting it, and even leaving food they expected him to take. He had his own followers, in other words.

Finkel exaggerates when he calls Knight “the last true hermit.” First off, there is no reason why someone today could not undertake the same goals as Knight. Second, and more important, Knight was hardly a “true hermit” in a historical sense. Finkel uncovers no motivation for his retreat. In the end, Knight seems merely eccentric. Caught stealing and jailed, he changes. He had shaved in the wild (p. 153) but quit shaving his head and face when he jailed so that he would look like a hermit (pp. 118, 178). He plays the role and, of the men I write about here, is the least adventurous. But he too savored the mix of comfort and danger his surroundings offered.

Finkel’s work refers to other works on the wilderness, including Krakauer’s book and the Life of Anthony, (pp. 201-2). Finkel also offers a brief history of the hermitic life (pp. 36-37). I was sorry to find that Pronenneke’s book is not mentioned in Finkel’s summary of wilderness- and hermit-related works (pp. 201-203).

Krakauer’s Into the Wild is an unsettling book. The hero, Christopher McCandless, was an unusually mobile young idealist. His disdain for his family and their problems was part of his motivation for taking long trips by himself. His family displayed extraordinary tolerance for his extended absences from home even when he was a teenager. He was also motivated by a desire to prove that he could be self-sufficient, which is to say not dependent on people and systems that had disappointed him. This is perhaps not unusual among those born into well-to-do families with professional backgrounds. His father was a NASA engineer.

After he graduated from Emory University in 1990, McCandless drove across the country, telling his family he intended to disappear for a while. They did not regard this as unusual—a fact I regard as unusual, I will say (p. 21). They evidently had other things to think about than his whereabouts and welfare. He circled around the southwest, finally abandoning his trusty Datsun after the battery failed (pp. 26-27). The Park Service found the car, jump started it, and used it for years. He worked in Las Vegas for a while in 1991 (p. 37) and went to Los Angeles.

Moving north, he worked on a wheat farm in South Dakota and established a friendship with Wayne Westerberg, the owner,. When asked about the young man, Westerberg later commented that McCandless was an outstanding worker but that he lacked common sense (p. 32, 63). The young man lived with other workers in Westerberg’s house; they became his new family, with Westerberg as the father-figure. He turned out to be McCandless’s main contact with the social world. As he hiked into the wilderness, McCandless claimed that South Dakota was his home, his native state. When he wrote to Westerberg, anticipating that he would not return from Alaska, McCandless told him that he was a great man (p. 69).

McCandless was intelligent and perceptive, but, as Westerberg believed, not sensible. Indeed, in some ways he was rash and poorly informed. He hitched a ride with a truck driver who knew Alaska and saw that McCandless was dangerously underequipped and poorly informed. In Krakauer’s account, which is partly based on the recollections of those with whom McCandless spoke, the young man exudes confidence. Although he receives several other warnings about his plans, he responds to them calmly and with assurance. When his death is reported—a media sensation, it turns out—many in the northwest remembered him, well and fondly.

For someone who believed so firmly in books that he carefully parsed an extensive plant guide, McCandless seems to have done little to acquaint himself with the wild world he was about to enter. In part this was deliberate. For example, he did not have a decent roadmap of the area he intended to inhabit (p. 174). To him, Alaska was full of empty spaces, but Krakauer points out that Alaska had been thoroughly charted. Lacking a good map, McCandless was unaware of such features as bridges and camps that might have saved his life.

The less he knew, it seems, the more persuaded the young man could be that he was a pioneer. McCandless roamed an imaginary landscape. Smith talks about those who die in the wild as if by plan, cases in which “the lack of preparation is quite deliberate” and death in the wilderness comes are a kind of peace (p. 239).

McCandless survived as long as he did because, like other hikers in that area, he had luck. He stumbled on a “magic bus,” as he calls it, an Anchorage public transportation vehicle that found its way into the woods. This ironic reminder of civilization far from the wild, is seen above.

Eventually McCandless ran out of food; he had been living on rice. He died of poisoning from seeds that had been contaminated by a fungus (pp. 192-94), something McCandless’s books would not have helped him with. He was scrupulous in avoiding plants and seeds known to be poisonous. And he was just 10 miles from a furnished cabin, but perhaps that does not matter. Someone visited the cabin not long after McCandless’s death and found that the place had been vandalized. Those who want to “free” the wilderness have been known to reduce such cabins to ruins. Krakauer doubts that McCandless would have done something like that without noting it in his diary.

McCandless was a good writer, insightful as well as honest, and a dedicated reader. One has to admire the confidence of a young man with no experience of the wilderness who sets off for Alaska with a small library in his backpack. He had a literary side. Books help him survive: War and Peace and others by Tolstoy; works by Thoreau and Gogol as well as by popular authors, among them Crichton and L’Amour. His mainstay, however, seems to be a book on edible plants (p. 162). Admittedly, 1990-92 was three decades ago, but even for his time McCandless seems to have been an unusually serious and well-read student. His experiment in Alaska failed after four months of difficult conditions, a sad end for a bright, educated man.

The fate of McCandless is the exception that proves the rule about the wilderness, which we also see in the lives of London and Thoreau. The hermit can live in isolation only some of the time, and only with the aid of the society he has tried to leave behind. McCandless was alone, but he needed freight trucks and highways and the apparatus of modern transportation to reach the wild.

That is to say, you can’t leave society behind without society’s help.

Is life in solitude better than social life? For those who embrace self-sufficiency in the sense Thoreau achieved it at Walden Pond, the answer is yes. There is merit in being your own company, without the distractions of friends and family. Free of phones and mail, say nothing of social media and email, the hermit is able to look more closely at the world around him. Water, hills, animals, the weather, all these and numerous other elements come to the foreground and look, sound, and feel brighter, more intense, more distinctive. Once in a while we all get a brief taste of this when there is a power outage or an empty battery.

But for how long are the hermit’s close-up views of the natural world and his solitude sustainable, to use a popular environmentalist word? The only hermit who tries to go it alone is McCandless, and he dies. He proved that a modern version of the ancient hermit’s life in the wilderness is impossible. Like those who met this young man, we remember him smiling, photographing himself near the end of his life, bearded, sitting on his magic bus, where his body, weighing 67 pounds, would lie until hikers discovered it (p. 14). We want to think he died happy.

McCandless writes that he was determined “to become lost in the wild” (Krakauer, p. 165). Of his journeys in British Columbia and Alaska, Smith writes that he allowed himself to be “swallowed by the landscape” (p. 79). Proenneke observes that nature can help you one minute and kill you the next (p. 87). I do not see these comments as expressions of nihilism or despair but rather as signs of spiritual ambition. To be swallowed or lost might sound dire, but either term could describe death to one’s self, death as ancient hermits like St. Anthony experienced it, as a passage leading to new life.

In the end, we will all be swallowed by the landscape, dust to dust. In this inescapable and real sense, going into the wilderness is an approach to death—going to the edge, where life meets death.

These campers and hikers struggle to experience nature unencumbered by guides, trails, and industrial tourism, seen in REI gear and helicopter tours of the Grand Canyon, which are all about overcoming nature in order to reach nature.

Adventurers are like extreme athletes, engaging in activities that carry a high risk of injury or death. In the wilderness they know that they are intruders, triumphant but unwelcome, out of place, and at mortal risk. They describe themselves as ecstatic and more alive than ever because they are on the edge. They are, in that sense, also closer to death than ever. If they are truly alone and unaided, as McCandless was, truly lost in the wild and swallowed by the landscape, their departure from this life is inevitable, natural, and, unlike the fall of a sparrow, unnoticed.

December 2024

Sources

Brooke, Christopher. The Monastic World 1000-1300. New York: Random House, 1974.

Burke, James Lee. Light of the World. New York: Scribner’s, 2013.

Finkel, Michael. The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit. New York: Vintage Books, 2017.

Hutchinson, Patrick. “Cabin”: Off the Grid Adventures with a Clueless Craftsman. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2024. Excerpts from the Wall Street Journal, Nov. 30-Dec. 1, 2024, C4.

Krakauer, Jon. Into the Wild. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

Mann, Thomas. The Magic Mountain. 1924. Trans. John E. Woods. Introduction by A. S. Byatt. New York: Knopf. 1995

Proenneke, Dick. One Man’s Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey. Ed. Sam Keith. 1973. New York: Vintage Books, 2018. Anniversary ed. Alaska Northwest Books, 2023.

Smith, Ken. The Way of the Hermit: My Incredible 40 Years Living in the Wilderness. New York: Macmillan, 2023.

——-. YouTube.

Snyder, EJ. Emergency Home Preparedness: The Ultimate Guide for Bugging in During Natural Disasters, Pandemics, Civil Unrest, and More. Skyhorse Publishers, 2024.

A fascinating read Allen. Thank you. I had never heard of many of these characters. I had a special interest since I have a bit of the hermit in myself!