Rafi Kohan’s Trash Talk: The Only Book about Destroying Your Rivals That Isn’t Total Garbage (2023) comes in the ugliest dust jacket I have ever seen. I began piling other books on it to keep it out of sight. Admittedly, the art supports one of Kohan’ central claims, which is that in sports the biggest mouth gets the most attention.

Muhammad Ali, anyone? Trash Talk has an effective punch-counterpunch structure. It sets out the gains of verbally abusing your rival in an athletic (or other) contest and then outlines the disadvantages of such confrontations. Talking trash is designed to distract or discourage an opponent, but it can also enrage him and boost his aggression (“aggro,” as some of Kohan’s subjects call it).

Over-the-top rivalry is a proven promotional technique (p. 37). Ali seized on it at the start of his career. He wanted to be the black guy that white guys could hate; his aim was to “make people angry at me” (p. 53). “Find the hate” is a mantra among trash talkers. They know that fans want to be part of the fight, not just to watch it, a point made by Colleen Aycock in Tex Rickard: Boxing’s Greatest Promoter (p. 40). Go to a boxing match and you will see men in the crowd leap to their feet throwing punches. They feel that the fight is theirs (a function of embodiment, as I note in Boxing and Masculinity, pp. 76-80). They show up so that they can find the hate.

Trash talk has a long history. Kohan refers to David baiting Goliath and to Epeius, builder of the Trojan horse, who claimed to be “the best boxer.” He said about his opponent, “I’ll tear his flesh to ribbons and break his bones. I hope his kin are here to take him away when I’ve felled him” (The Iliad, book 23; quoted by Kohan, p. 4).

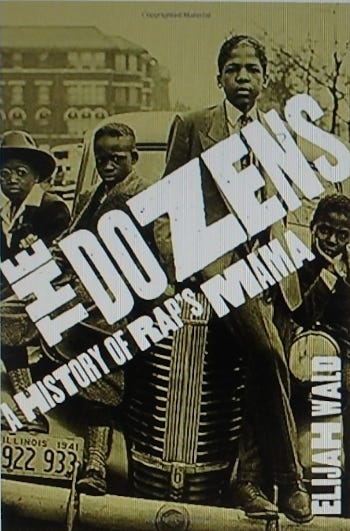

Closer to home, trash talking has a strong connection to Black tradition of “the Dozens,” a “game of exchange” of insults between contestants who are “trying for verbal and creative supremacy via any vulgar means necessary” (Kohan, p. 16). In his 2014 study of “the Dozens,” Elijah Wald notes that the form was sometimes explicitly sexual, that being one of the hallmarks of rap (The Dozens: The History of Rap’s Mama; the paperback edition is Talking ‘Bout Your Mama: The Dozens, Snaps, and the Deep Roots of Rap).

Trash talk is often seen as a friendship ritual with “a few sharp edges,” Kohan writes. It is a linguistic code that is recognized by multiple terms. For example, “signifying” refers to direct insults, whereas “the Dozens” refers to insults directed at one’s family.

Trash talk sometimes ceases to be a game. Referring to “the Dozens,” Zora Neal Hurston describes the exchange as “a risky pleasure” because it could lead to real violence (Kohan, p. 15). Recently the rivalry between fans of two stars of the Women’s National Basketball Association generated death threats and online racial abuse, according to Rachel Bachman. The excitement has made it too dangerous for the teams to travel on commercial flights.

Caitlin Clark (Indiana Fever) and Angel Reese (Chicago Sky)

Most commentaries see trash talk as positive because it is motivating to both the giver and the receiver. Kohan makes an important contribution by describing what trash talk can do to the trash talker. An MAA fighter named Josh Dempsey (known to prison authorities as John Gormley) was big on trash talk “just for show.” However, he found that “the line between movie and real life began to fade. At some point, he suspected it wasn’t actually an act at all—he was losing his grip on which part was which” (pp. 61-65). Trash talking can give rise to self-loathing and second thoughts.

Others have made that discovery. “Not everyone is meant to be a heel,” Kohan writes. Dempsey’s (i.e., Gormley’s) view is confirmed by the experience of superstar LeBron James. He decided to give up the bad-guy role because it “turned me into somebody I wasn’t” (p. 60). The person turns into the trash-talking persona.

Among the historical figures who engage in trash talk is the jester. Beatrice Otto points out that the jester was an “adviser and critic,” not merely an entertainer. His “family tree” includes “musicians and actors, acrobats and poets, dwarfs, hunchbacks, tricksters, madmen, and mountebanks.” Among dwarfs and hunchbacks, we might imagine that the jester’s physical difference from his patrons was protective and might have reduced the risk of being an outspoken critic of the powerful.

An important figure in the tradition of the jester is Rigoletto, who is the unhappy entertainer at the center of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto (1851). The opera is set in the Italian Renaissance but is often updated to the modern era. Recent productions have set it in Las Vegas, fascist Italy, and even on The Planet of the Apes. Trash talk works in all those environments.

Rigoletto suffers from kyphosis, a spinal disorder that causes the upper back to be rounded to a forward position. His job is to make people laugh by deflating their egos. They invite and enjoy his provocations but they also resist them and resent him.

Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto, Lyric Opera of Chicago (2017)

Rigoletto is in the service of the Duke of Mantua, a notorious womanizer who sings two of Verdi’s most famous arias, “This one or that one, all the same to me” (“Quest o quella,” Act 1) and “How fickle women are” (“La donna è mobile,” Act 3). Women are not all the same to Rigoletto, who trusts women to be constant. He has a beautiful young daughter named Gilda. He jealously guards her and keeps her isolated, allowing her to leave the house only to go to church with her older attendant.

Rigoletto and the Duke are not, like Gormley or James and their opponents, playing on different teams. The Duke and the jester, we might say, are playing different sports. How does trash talk work between them? Talk isn’t trash unless it cuts close to the bone. You can call somebody a turkey without expecting a response other than a laugh. Suggest that somebody is timid, however, and you might have a fight on your hands.

Rigoletto’s bone, his vulnerability, is not his deformity or his subservient position in court; it is, rather, his determination to control his daughter’s life. His excessive dependence on his daughter is plain. Gilda is everything to him, he says: “My country, family, and friends, the whole universe you are to me” (p. 16, act 1). If she were his wife, we would call him uxorious. Whereas the Duke sets no value on women, Rigoletto sets too high a value on the only woman in his life. His feelings for Gilda seem close to the feelings he had for his wife when she was alive.

The Duke has no obvious vulnerabilities. He sets out to please nobody but himself and does not defer to someone more powerful than he is. Like him, his courtiers seem to regard women as no more than tools or weapons. Rigoletto himself, in mocking men whose wives the Duke has seduced, seems to do that himself.

Rigoletto has progressed one step beyond trash-talkers Gormley and James. When they realized that trash talk was deforming them, they backed off. Rigoletto’s trash talk has deformed him as well, affecting him more than those at whom he directs it. He knows and admits that this is the case, but he does not back off. He can no longer differentiate his persona as jester from his person as father.

The jester and his audience of courtiers are in competition. Both answer to the Duke. To make others laugh is his vocation, the jester says. But he finds that he is not to be allowed to “do anything but laugh.” His profession seems to have captured him. He cannot make others laugh without laughing himself. He claims that “weeping, the possession of every man, is denied [him ].” But this can be true only because he believes it to be the case. It is neither a condition of his employment nor one of its effects. He has suppressed his empathy in service to his instinct for attention.

The ever-amorous Duke announces that he would like to pursue two women, the wife of Count Ceprano and an unknown woman he has seen in church. Rigoletto jumps in, mocking Count Ceprano and other men whose wives the Duke desires. Then he unwisely crosses a line that the trash talker must respect—the line dividing words from actions.

Rigoletto insults Ceprano and then suggests that the courtiers abduct Ceprano’s wife. He also suggests that the Duke imprison Ceprano to get him out of the way. Amused, the Duke warns Rigoletto that “you always carry your jokes too far” and that one day he himself might be the target of someone’s anger (p. 9). Rigoletto responds that as the Duke’s protetto or protégé he will be protected. But the Duke cannot protect Rigoletto from his own feelings when they are provoked.

At just this point another courtier, Monterone, bursts in. He has discovered that his daughter has been seduced by the Duke, whom he curses. Rigoletto mocks Monterone’s grief, and Monterone in turn curses him. Rigoletto has long feared for his own daughter’s safety. Knowing now that both Monterone and Ceprano have been targets of the Duke, and deeply disturbed by the curse, Rigoletto takes a precaution. He meets with an assassin named Sparafucile. Sparafucile hypothesizes that Rigoletto has a mistress and rival and that he will need a swordsman. Thinking his need to protect Gilda, Rigoletto listens.

“We are equals” (“Pari siamo”), Rigoletto says after his conversation with Sparafucile. “The tongue is my weapon, the dagger his! To make others laugh is my vocation—his to make them weep. O human nature, what scoundrels you make of us. O rage, to be deformed—the buffoon to have no play! . . . You sycophants, you hollow courtiers! If I am deformed, it is you who have made me so” (p. 13). Rigoletto fails to grasp the practical significance of two points. First, Sparafucile has a sword; Rigoletto has only speech. Second, Rigoletto has deformed himself by abandoning what we might call fellow-feeling.

Rigoletto keeps much from his daughter, never imagining that she keeps things from him. At church, Gilda has fallen under the Duke’s roving eye. He has her followed, then bribes her servant and gains access to her house, where he pretends to be an impoverished student. The Duke does not know that she is Rigoletto’s daughter. Gilda is charmed and falls in love with a schoolgirl’s abandon. The Duke, the would-be student, tells her his name is Walter Maldé. They swear their love. When he is gone, she sings her famous aria, “Caro nome” (“Dear name”), saying that until death her heart will beat for him alone. In this, it can be said, she is prescient.

Gilda (Ekaterina Siurina; Royal Opera House, 2014)

The courtiers decide to act on Rigoletto’s proposed scheme to abduct the wife of Ceprano. They persuade Rigoletto to come with them. He wears a mask and a blindfold (the blindfold is unexplained, except as a necessity of the plot; Rigoletto seems to believe that it is very dark and not to realize that he has been blindfolded). They tell him they are at Ceprano’s house. But in fact they are at Rigoletto’s house. He holds the ladder as they enter and capture Gilda. Thinking that she is Rigoletto’s mistress, they take her to the Duke.

This is the courtiers’ revenge. Rigoletto talked trash about them; now they talk trash about him. It has been Rigoletto’s aim to laugh at others. Now they are mocking him. “Let him be caught in his own trap,” the courtiers say. “The jester who constantly makes sport of us shall now, in his turn, be subject to our laughter” (p. 24).

When Rigoletto discovers that he has been tricked and that it is Gilda, not the Countess Ceprano, who has been kidnapped, he rushes to court. He arrives just as Gilda emerges from the Duke’s bedroom. Everyone is shocked to discover that she is Rigoletto’s daughter. Gilda confesses her “ruin and dismay.” After she explains what has happened, Rigoletto replies, “What must be done I will quickly do” (p. 33). Gilda tells her father that she loves her seducer and that she cannot help it (p. 34). She even asks that her father pity the Duke. At the end of the opera, she will give her life so that the Duke can be spared.

We see that Rigoletto’s role as a trash talker differs from that of Dempsey and James. Athletes might talk trash about a girlfriend, a wife, or even a mother. The men they are ribbing might talk the same trash back. If either adversary did more than talk, however, the conflict would move to a new and dangerous level. Whereas James and Dempsey stood on equal footing with their opponents, Rigoletto is far inferior to the Duke whom he wants to thwart. Apart from his tongue, Rigoletto is powerless. His tongue might be cutting, but it is not a sword.

Many regard Rigoletto’s chief offense as his excessively protective attitude toward his daughter, Gilda. In feminist interpretations she is seen as a young women hungry for her share of sex and power. A recent production at Lyric Opera of Chicago took this ubiquitous “girl power” approach to extremes and involved Gilda in a sword fight with Sparafucile.

A review by Lawrence A. Johnson commented on this egregious move, the invention of director Mary Birnbaum. “The director saved her worst ideas for the climax of the opera,” Johnson wrote. “Rather than the sudden blackout Verdi requests when the self-sacrificing Gilda enters Sparafucile’s den to her doom, Birnbaum has the character engage in an extended sword fight with the veteran assassin (and, incredibly, has the slumbering Duke suddenly awaken and join in). Right. The innocent, naive and cloistered Gilda is instantaneously transformed into a master swordsman like Brienne of Tarth.” Brienne is the woman warrior of Game of Thrones, she being the kind of figure directors today think of as historical.

Rigoletto protected his daughter from all knowledge of the world, preserving her innocence and delaying her maturity. A stranger to emotion, she easily falls for the Duke’s mask of charm and poverty. Even when she finds out that the “student” was in fact the Duke, and later, when she sees him making love to another woman, she remains faithful. All the resources that might save her—self-respect, wariness, skepticism—are beyond her ken.

Gilda did not need to be armed with the sword that Lyric director Mary Birnbaum put in her hands. Gilda needed to be armed with common sense. Helping her acquire common sense was her father’s duty. But it turns out that, like any father, Rigoletto could not give away what he did not have.

Gilda reminds me of Desdemona, another of Verdi’s unfortunate women, the famous victim in his last opera, Otello (1887). After Otello strangles Desdemona, her attendant, Emelia, rushes in to ask the dying woman who has done this to her. Desdemona replies, “No one, myself.” Gilda does better. When Rigoletto asks who has stabbed her, she says “I am guilty. Too much I loved him—now I die for him” (p. 45). Rigoletto replies, “By my hand has she fallen.”

Father and daughter hold to separate truths. In a strangely satisfying way, both are correct. That said, no one responsible for raising a young woman looks good when she makes a fool of herself over a man.

Sources

Aycock, Colleen. Tex Rickard: Boxing’s Greatest Promoter. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2012.

Bachman, Rachel. “Tensions Amid WNBA’s Boom.” The Wall Street Journal, Sept 16, 2024, p. A14.

Frantzen, Allen. Boxing and Masculinity: Fighting to Find the Whole Man. Bookbaby, 2022.

Johnson, Lawrence A. “Stellar cast shines as Lyric Opera opens season with a near-great ‘Rigoletto.’”

Chicago Classical Review, 25 September 2024. https://chicagoclassicalreview.com/2024/09/stellar-cast-shines-as-lyric-opera-opens-season-with-a-near-great-rigoletto/

Kohan, Rafi. Trash Talk: The Only Book about Destroying Your Rivals That Isn’t Total Garbage. New York: Hatchett Book Group, 2023.

Otto, Beatrice K. Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester around the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Verdi, Giuseppe. Rigoletto. The Opera Libretto Library. 3 vols. New York: Crown Publishers, 1980. 3:1-47.

Wald, Elijah. Talking ‘Bout Your Mama: The Dozens, Snaps, and the Deep Roots of Rap. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

9/24

A revealing essay.

Feminism cannot resist turning every female possible into a Raging Athena, no matter the female's disposition. But the rage, in this case, in is the heart of the director. Feminism is a curse of an ideology and cult, deforming the minds, hearts, and spirits of females.

I really enjoyed this one, especially since I was a teen during most of Ali's reign. Fascinating info on trash talking and a riveting story of Rigoletto. What a story and wonderfully instructive on this topic. Thanks Allen!