Boxing fans often disagree with critics about what makes a boxing movie great, and sometimes the critics disagree with each other. Just before the recent Academy Awards, Wall Street Journal critic Rich Cohen wrote about the 1977 Oscar contest, explaining “Why ‘Rocky’ Deserved to Beat ‘Taxi Driver’ for Best Picture” (March 9-10, 2024. p. C2). Few critics thought so at the time. Cohen has ideas about what makes one movie better than another and also what makes one boxing movie better than another.

Here I consider his criteria with reference to Ron Howard’s “Cinderella Man” (2005). This is story of James J. Braddock, world heavyweight champion 1935-37 (born 1905, died 1974), a boxing film that quietly explores what it means to be a winner as a man. (Braddock, below; Damon Runyon thought up the Cinderella business.)

“Rocky” vs. “Taxi Driver”

“Nothing gets the critics going like ‘Rocky’ director John Avildsen lifting the statue as [Martin] Scorcese looked on,” Cohen writes. He lists the strong points of Avildsen’s movie to explain why it is better than “Taxi Driver.”

“Rocky” is superior because, like boxing itself, the film is “artless.” Cohen describes Scorcese’s work in “Taxi Driver” and in other films as striving for Art “with a capital A.” Avildsen, by contrast, was a “middle-aged, Midwestern workhorse” with a list of mediocre films. But his no-nonsense approach was “functional,” Cohen writes, “which is what boxing is all about—forget the flashy moves, just put the bastard on the canvas.”

My answer to that: let’s talk about Muhammad Ali, a great boxer and a master of flashy moves. Anybody who has trained for a while and then sparred a better boxer knows that art in boxing can be as important as power. Flashy moves, made for their own sake, waste your energy. Flashy moves that distract your opponent, however, can help you win.

Cohen then argues that “Rocky” is superior because it adheres to “a sports writing axiom” according to which the subject of the story should be able to understand the story itself. Maybe this is true for sports stories. But I think of Ulysses and wonder if Molly or Leopold Bloom could have followed James Joyce’s tale.

Scorcese made his own boxing movie, “Raging Bull,” about Jake LaMotta. Just four years after he lost to “Rocky,” Scorcese lost the best picture Oscar to “Ordinary People” (Robert Redford’s debut as a director). Cohen writes that he “can’t imagine” LaMotta “sitting through Scorcese’s movie.” But Cohen believes that LaMotta would have had no trouble sitting through “Rocky.” Cohen overlooks something important, which is that LaMotta trained DeNiro for “Raging Bull.” Arty or no, “Raging Bull” would have drawn LaMotta’s attention (LaMotta, below).

The third point Cohen offers is that “Rocky” worked against the prevailing “bleak pit” of the times, when “confusion and injustice” were plentiful (as they are in “Taxi Driver,” to be sure). “Rocky” has simple clarity. The boxer did not win the big fight, but his goal was to last the full 15 rounds, and that he did, thereby taking the shine off a champion thought to have been invincible. It was a very modern way to look at victory. It did not deliver a Cinderella moment but instead a shared moment, even a reconciliation. A good boxing movie, then, is a movie about modest hope, not about transformation.

Cohen’s final point is that a good boxing movie is set in “the world of everywhere else” and takes place outside Manhattan (“Taxi Driver”) or the Bronx (“Raging Bull”). “Rocky” is set in Philadelphia, apparently remote enough to constitute an “elsewhere” for New Yorkers.

Critics disagree, but not always. Entertainment Weekly’s list of the 25 best boxing films puts “Raging Bull” first and “Rocky” second. “Cinderella Man” is in 16th place. A note describes it as a beautifully finished work that depends too much on the clichés of the genre. “Raging Bull” and “Rocky” are dependent on the same conventions, of course, but deliver them with blunt force, not with Howard’s characteristic light touch.

One thing not at stake in rankings like this one is how films represent boxers as men. Let’s see how “Cinderella Man” stacks up against Cohen’s criteria for boxing films, and then focus on the masculinity of the boxer at the center of the picture.

Arty?

I wouldn’t call “Cinderella Man” an “arty” work, although it uses flashbacks. Its set and costume colors are controlled to create a Depression-era atmosphere—nothing loud or primary. This design works subconsciously and creates a feeling of plainness and unobtrusive restraint. Art, sure, but not art you notice—so great art, but not arty.

Who will “get” the movie?

The residents of Bergen, New Jersey, Braddock’s home, and other ordinary people who populate the film, would certainly understand “Cinderella Man.” Some moments seem abrupt because phases of Braddock’s history are elided; it is a long film in any case, two hours and 20 minutes, about 30 minutes more than what is considered the best length. Nonetheless, you can’t miss its power.

Too New York?

The fights are set in Madison Square Garden (the movie was made in Canada). These scenes are successfully mixed with dark glimpses into homes and churches. A few touches of glamour (e.g., night clubs) underscore the struggle of the impoverished millions outside the small world of boxing. We could be in any city, looking at its bread and soup lines, its unemployed, hungry, and homeless.

The “bleak pit”?

Rather than work against the “bleak pit” of its era, as Cohen says “Rocky” does (the “bleak pit” of the 1970s), “Cinderella Man” works with the bleakness of its time, and this is the film’s strongest achievement. It shows Braddock to be one of those rare boxers—his contemporary, Joe Louis (1914-1981), was another—whose fights meant something to almost everybody, and not just to the people who knew him. Cinderella went from rags to riches; she rides off with her prince, leaving her heartless sisters, and us, behind. Cinderella Man has a more complex experience, going from victory to loss, to injury and poverty, and then, slowly, back to victory and triumph, but with his future left open. This kind of halting, shaded experience mirrors the lives of ordinary people, many of whom dismiss narratives of triumph as fairy tales—as Cinderella stories. Braddock’s life was not really a Cinderella story.

(Above: soup and bread in New York City, c. 1932; courtesy of National Archives. Gentlemen: note the suits, ties, and hats for those in line, all men; they remove their hats when they are served.)

“Rocky” (and its sequels) and “Raging Bull” are stories of personal transformation. They are famous for iconic scenes that drive home themes of alienation, rage, betrayal, and revenge. These are among the demons that haunt the boxers at the center of the films and that are sometimes exorcised by the boxers’ wins and losses. We see this resolution in numerous boxing novels and boxing films.

“Cinderella Man” takes a much lighter and broader approach, giving the boxer, his family, and his people a shared opponent, the endless Depression. The movie then uses the boxer’s come-from-behind success—his Cinderella potential—to bring his people with him as he rises. In some of the movie’s most powerful sequences, they understand that he is fighting for them. They pray for him, even though he can do nothing for them financially. They pray for themselves at the same time. Will he make it? Will they? In their minds, he gives them a second chance like the second chance he’s been given. He gives them some hope. Nobody else does.

The masculinity at stake in “Rocky” and “Raging Bull” is based on the man as a fighter. “Cinderella Man” looks at the boxer as a man, a family man in particular, one of us, not one of them.

Braddock fights with a broken hand, battling his own pain as he battled his opponents in the ring. He has to get paid. His most degrading moment is not the early end of his boxing career, however, and his subsequent, miserable search for a job. His most degrading moment is his realization that he cannot feed his children. They want more to eat. He can’t provide it because he can’t work. He can’t fight because nobody thinks he’s worth watching. He can’t work because other men are stronger and younger and get chosen for the few jobs there are. He’s a dockworker hired by the day. So, it seems, is everybody else.

His most manly moment, it follows, comes after his utterly unexpected string of victories over better boxers. Thanks to his tireless trainer, Braddock comes out of the losing streak that caused him to be written off. He racks up unexpected wins against title contenders. Then he gets to fight the dangerous Max Baer. Against the ten-to-one odds, Braddock wins the heavyweight title.

Great though it is, in history and in film, his victory over Baer was not Braddock’s best moment. That moment in the film is his chance to return to the unemployment line and this time, to the shock of the clerk, repay, to the penny, what he had been given. His victory is not pumping his fists in the ring but handing over bills and coins. He squares himself with the society that saw him through his worst moments, his loss of independence and his failure to keep his promises to himself and his family. Braddock honors the system that saved his family and saved him as a family man.

The shaded, understated, yet engaging narrative strategy of “Cinderella Man” is possible because Braddock was not a star. He had 88 fights and a mediocre record: 52 wins, 26 losses, 10 draws or no-contests. Compare him to his contemporary, Joe Louis, who took the heavyweight title from him in 1937; Louis had 69 fights, with 66 wins and 3 losses. Louis was a star.

Braddock’s career began well but steadily declined. In his first 20 fights (1925-27), he had 17 wins and 3 draws or no-contests. His next 20 fights (1927-28) yielded 14 wins, 3 losses, and 3 draws or no-contests. But in his next 40 fights, over five years (1928-33), he had only 15 wins, against 22 losses, one draw and two no-contests.

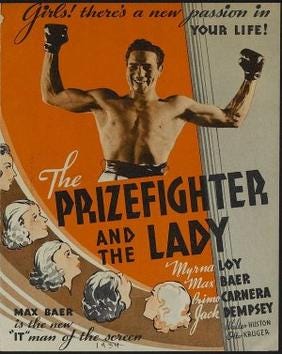

Then he made his famous comeback, with three big wins in a row over men seeking the heavyweight title, Corn Griffin, John Henry Lewis, and Art Lasky (1934-35, Lasky above, left, with Braddock), leading up to the culminating fight in the movie, his victory over Baer in 1935. Baer, like several other great boxers, went on to have a career in film. (Below: Max Baer and Myrna Loy; other top-flight boxers in the film are Primo Carnera and Jack Dempsey.)

Braddock defeated Baer by decision, not by a knockout. In film, as in life, a victory by decision makes the most of the drama inherent in boxing. After a career of ups and many down, Braddock became the world heavyweight champion. He lost the title to Louis in 1937. He had had no matches between his victory over Baer in 1935 and his loss to Louis. After that, he had just one more fight (which he won), in 1938.

“Cinderella Man” leaves the boxer and his ecstatic family in a blizzard of confetti. In life, Braddock went back to work. Unlike so many boxers, he did not sustain brain damage, even in his fight with the dangerous Baer, a ferocious puncher, one of whose opponents died during the fight (Baer’s character, many feel, is distorted in the film). Braddock went from strength to strength. He enlisted in the Army in 1942 and served as a first lieutenant in the Pacific, where one of his duties was to train men in hand-to-hand combat. After the war he became a marine equipment supplier and worked on the construction of the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge (1959-64). He died in 1974.

Boxers will find an unexpected gift in the movie. For his role as Braddock, Russell Crowe was coached by none other than Angelo Dundee (d. 2012), the most famous boxing trainer and corner man in U.S. boxing history. Dundee trained Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, George Foreman, and several other world champions (some seen with him, below).

In the movie, Dundee appears as Angelo, the cornerman. He works with Paul Giamatti, who plays Braddock’s trainer. The extra features on the DVD show Braddock, Baer, and other boxers in action. These jaw-dropping historical materials helped shape Crowe’s impressive boxing performance as well as that of his ring opponents. Ron Howard’s comments on deleted scenes suggests how finely the film balances its martial mojo against Howard’s desire for a restrained and patient portrait of the boxer as a man.

Everything we associate with James J. Braddock points to the best of masculinity: boxer, longshoreman, family man, naval officer and trainer, construction equipment expert. The movie is based on Jeremy Schaap’s 2005 book, Cinderella Man: James J. Braddock, Max Baer and the Greatest Upset In Boxing History. Like the movie, the book shows that Braddock’s success depended on discipline, responsibility, generosity, and modest optimism. Masculinity was Braddock’s greatest achievement. His lessons in life are available to every man and offer special inspiration to every man who boxes.

Thank you for this wonderful review and analysis. I have always enjoyed Rocky and now look forward to watching Cinderella Man.

Thank you Allen for another fascinating read. I was struck by the contrast of the public view of masculinity then and now. What a mess we are in.