A power couple is “a partnership where both individuals actively contribute their strengths, skills, and resources,” or so AI tells us. Although the partners make joint decisions and contribute to a common cause, they usually have separate careers.

Consider the great French singer Edith Piaf (1915-1963) and one of her most famous lovers, the boxer Marcel Cerdan (1916-1949). Piaf was part of many power couples. Her lovers included the actors Yves Montand and John Garfield; the singers Jacques Pills and Eddie Constantine; the bicycle champion André Pousse; composer Norbert Glanzburg; and song writer Georges Moustaki. There were more. She married twice; one husband, Théophanos Lamboukas, was a gay man 20 years younger than she was.

Cerdan and Piaf

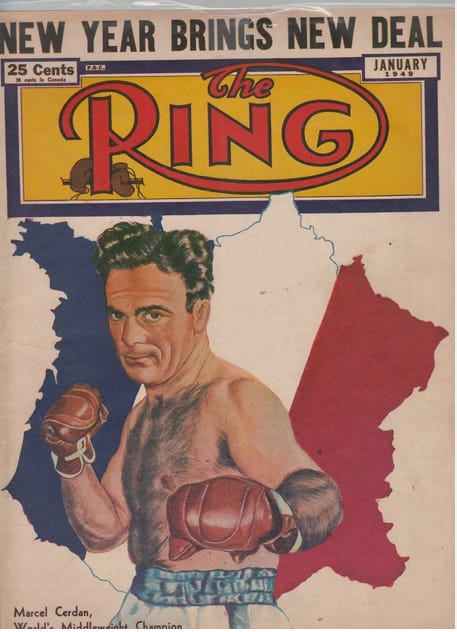

In the company of these men, the two athletes, Pousse and Cerdan, stand out. Pousse went on to make many movies. Cerdan, the man thought to have been her Piaf’s true love, did not have a second career. He didn’t have the chance. Between 1934 and 1949, he compiled an astonishing record of 100 wins and four losses. He died in a plane crash in 1949 at age 33.

Margaret Crosland notes that Piaf sought to manage the lives and careers of her lovers. She completely remodeled the speech and style of Yves Montand, for example, forcing him to abandon his Stetson hats and checkered shirts. She also helped him lose his Marseilles accent (pp. 80-81).

But Piaf’s powers had limits. Pousse resisted Piaf’s strategies and made his own efforts to reform her drinking and her spendthrift habits. He had no more success with her than she with him (pp. 118-19).

Piaf also failed to educate and transform Cerdan, an Algerian who met Piaf in 1947 and who, like Pousse, eluded what Crosland calls Piaf’s “ambitious Pygmalionism” (p. 96). Cerdan had only a few years of formal education. Yet Piaf tried to get him to read André Gide’s L'immoraliste and Le retour de l'enfant prodigue, books that were better fare for her than for him. He seems to have read a bit nonetheless, asking if Gide wasn’t “un peu pédé” (a bit gay; see Grimault and Mahé, p. 109). The biography by her friend Simone Berteaut (also known as “Momone”) makes it clear that Piaf was a powerful distraction for Cerdan and that she turned him into something of playboy, not to his benefit as a boxer although certainly to hers as a popular singer (p. 305).

The energy of this power couple worked both ways. Cerdan’s influence on Piaf did not extend to her philosophy or to her choice of novels. But it was lasting nonetheless. On the night she learned of his death, she went ahead with a performance in New York, telling the audience that she was singing for him alone (Crosland, pp. 99, 122). Cerdan’s death silently informed her stories of loss and disappointment, the kinds of sentiment she was famous for. Piaf performed for another 15 years after Cerdan died.

In a sense, her art kept his memory alive. “It may be,” Berteaut writes, “that because he died he remained her only love and wasn’t returned to the ranks like all the others,” an ambiguous comment that points to the singer’s use of Cerdan’s death (p. 310).

For one person who knows Cerdan’s name today, there are probably one—or ten?—thousand who know hers. When Cerdan was alive, however, he had a tremendous following. In 1939, after his two victories over the Italian Saverio Turiello, the streets of Milan were jammed with Cerdan’s fans, even though Milan was Turiello’s home town. Cerdan was a hero in Casablanca, where some 70,000 people turned out for a Mass after his funeral (Crosland, p. 100).

Cerdan was born in Algeria and was raised to be a boxer. His aptitude for the sport was apparent by the time he was just eight years of age. Boxing was the way he could help to support his impoverished family. His father, a butcher, managed the first phases of Cerdan’s career. Gentle and polite, the boxer had had 28 fights before he began to box in France in 1936. He ended his boxing career with an outstanding record of 110 wins and four losses. His career was peaking when World War II broke out, and this disruption is thought to have limited his standing in the international rankings of boxers.

Memory of the boxer’s death took an unusual turn in 2016, with the appearance of Constellation, a novel by Adrien Bosc. Constellation was the name given to the relatively new kind of plane in which Cerdan died. (Bosc who won the Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie francaise for the work.) The book was praised by one reviewer for taking into account some of the unknown people who died in the crash as well as those who were famous (Leibowitz). Reviews of Bosc’s book gave the reading public a chance to learn something about the boxer, who has been dead for 75 years.

Piaf’s public was much lager than Cerdan’s. One of the great stars of the twentieth century, she stands in a long line of cabaret singers whose fame hers has eclipsed. They include her contemporaries, Marie Dubas and Yvette Guilbert, who are known today only to specialists of les chanteuses realistes.

Songwriters rushed to give these chanteuses material. The subject matter was often life in the poor parts of Paris. The writers used ordinary language and popular slang; their song had nothing to do with the charm ordinarily associated with the city. They also differed from the broad, brassy cynicism found in the lyrics of Marlene Dietrich, who was one of Piaf’s close friends. Piaf’s songs are to Paris what rap is to great cities today. Both musical forms probe the underside, the belly of the beast.

Piaf and Cerdan used the same management company in Paris. The Organisation Sportive et Artistique (OSA) handled professional athletes and artists. OSA was part of Le Club des Cinqs, which included a large nightclub. Piaf sang there, and that is where, it is assumed, the singer and the boxer probably met. Cerdan is said to have been an excellent dancer, a musical side certain to have been important to Piaf.

Cerdan and Piaf were acquainted by December 1946, when he went to New York for his first fight in the U.S. She listened to his fight with Georgie Abrams on the radio at Le Club des Cinqs. When she heard that Cerdan had won, she sent a telegram to congratulate him. It was his eighth fight that year.

In 1946 Cerdan became European Middleweight Champion. When he defeated Tony Zale in New York on September 21, 1948, he became World Middleweight Champion. Piaf was at ringside for his fight with Zale. But she was not present at Cerdan’s last fight, in which he was defeated by Jake La Motta (“Raging Bull”) and lost the titles he had taken from Zale a few months before (June 16, 1949; the titles at stake: NYSAC, NBA, and The Ring middleweight titles).

On October 27, 1949, on his way to train for a rematch with La Motta. Cerdan left Paris on an Air France flight. The rematch had been postponed from September to early December because Cerdan had injured his shoulder. Cerdan had planned to come to New York later, but Piaf, in an impulsive fit that was utterly typical of her solipsistic behavior, urged him to come earlier. He had planned to travel by ship, but she was desperate to see him and asked him to fly.

The plane left Paris-Orly at 20:05 for New York, with an intermediate stop at Santa Maria, Azores. At 2:51 the flight reported flying at 3000 feet with the airfield in sight. But after they acknowledged landing instructions, the crew fell silent. It took hours to discover that the Constellation had struck Redondo Mountain at an elevation of 900 meters.

The cause was determined to have been crew error. The official report reads as follows: “Failure to carry out either of the approach procedures for Santa Maria airport. False position reports given by crew. Inadequate navigation. Failure to identify Santa Maria Airport, when flying in VFR [Visual Flight Rules] conditions.” Cerdan’s body was identified in the wreckage by an initialed Cartier watch that Piaf had given him.

His death was by no means the end of her involvement in his life. Cerdan carried on his affair with Piaf even though he had a wife, Marinette, and three sons. One of them, also named Marcel, pursued a boxing career and became Piaf’s friend. He wore the Cartier she had given his father.

After Cerdan’s death, Piaf began corresponding with Marinette, who answered Piaf’s letters and came to Paris to see her. In 1969 Marinette published a book about her husband. Piaf had taken in Marcel junior while he trained for boxing. He lived with her for eight years. She commented that she felt like his mother. This is a role that few people would assign to her. But it is a role easily understandable in that it provided her a place in Cerdan’s history. Eventually all three of the Cerdan sons went to school in Paris, which had become their home away from home (Crosland, p. 145).

The three books about Piaf that I have read, and the quite good 2007 movie about Piaf, La Vie en Rose, make no reference to her maternal side, there being so much else to dig into. But for me Piaf’s handling of the Cerdan family is part of her role as partner in a power couple that was one of the great odd couples of both boxing and music.

Cerdan had given Piaf a lot, there is no question, but she did more than mourn him. It is not the role of the mother that she grew into, I would say, but rather Cerdan’s role as the family’s caretaker and provider. She was also, in her own fashion, educator of the children once they came to Paris.

Everyone comments on Marlene Dietrich’s masculinity, which, given her fondness for male attire, cannot be missed. She was a mentor to Piaf. But I do not believe I have ever heard or read any comments about the masculinity of Piaf, who had none of Dietrich’s commanding presence (there is a wonderful scene with the two of them in La Vie en Rose). Masculine she was not, but Piaf found what can be caller her paternalistic side, if not her fatherly side.

Decision and responsibility seem to sit lightly on her sholders. I trace Piaf’s style and performance choices to her disastrous upbringing. She was abandoned by her mother when she was eight. She accompanied her father, Louis Gassion, a street acrobat, as he toured northern France. When they returned to Paris, she began to sing in the streets. Piaf had a half-sister, Denise, born to her father and one of his many mistresses. Another woman, unrelated to Piaf, named Simone Berteaut, claimed to be another of Louis’s children and hence to be Piaf’s half-sister. Simone’s mother did marry Louis, Piaf’s father, but it not certain who Simone’s biological father was. Berteaut wrote a fulsome biography of Piaf. Piaf had a daughter with Louis Depont, with whom she lived for a while; the child died at age two (Crossland, p. 18). She knew her father, and she knew motherhood, and, in addition, many lovers.

Cerdan’s upbringing, compared to Piaf’s, was focused and traditional. He knew nothing about singing and Piaf knew nothing about boxing. What strengths, skills, and resources did they share, and what did each contribute to their partnerhip? Given the shortness of their time together, and the distances that often separated them, we cannot expect too much from either partner.

Cerdan was more the receiver than the maker of romantic gestures. After his victory over Zale, for example, Piaf had 500 roses sent to his room, a big order by any standard and an amusing role reversal given the historical conventions of sending flowers.

Piaf has a strong image, but she does not seem to have been, at heart, a fighter. At least that is what her music suggests. It is not about resistance or revenge but rather about sadness and alienation, even indifference. Look at the sentiments of “Non, je ne regrette rien” (“I regret nothing”):

No, I regret nothing

Neither the good that was done to me

Nor the evil, I couldn't care less

No, nothing at all

No, I regret nothing

It's paid for, swept away, forgotten

I don't care about the past

In a different spirit, “La vie en rose” (“Life in pink”) is about submission and satisfaction, not desire:

When he takes me in his arms

He speaks to me softly

I see life in pink

He tells me words of love

Words of everyday life

And it does something to me

He’s entered my heart

A piece of happiness

I know the cause

Of interest here is the phrase, “words of love / words of everyday life,” a significant juxtaposition and a plain rejection of romance. This is as far from the hard edges of survival as one can get. “It does something to me” points to an effect without specifying what it is. “Life in pink” is not about analysis or comprehension but rather about comforting and agreeable sensation.

Piaf was not educated, but she took it upon herself to educate others, insisting, for example, that the journalist Jean Noli read the theology of Teilhard de Charin (Crosland, p. 182). She seems to have thought that whatever she knew about she actually knew.

What we can conclude from her long string of misfortunes (and I have left most of them out) is that, through her suffering and the neglect she experienced, Piaf came to understand what it took to survive. She did her best to look like a white-faced and fragile waif; yet comments on her singing always emphasize the core of steel at the heart of her sound and of her stage presence as well. She never wanted to share the stage. That is not a mark of frailty.

When Cerdan died, leaving her alone, she did not collapse. She continued to build her career. As we have seen, she contacted Cerdan’s widow and soon took Cerdan’s place as manager of his family. She had always yearned to manage him. In the end she was able to do much better.

Cerdan was regarded as France’s most celebrated boxer since Georges Carpentier (who famously fought Jack Dempsey in 1921). Some wanted him buried in Père-Lachaise with Piaf, but this bad idea, fortunately, was never realized. His body was moved from Casablanca to Perpignan’s South Cemetery, where there is a large memorial to the Cerdan family.

However much they meant to each other in life, the distance between the boxer and the ballad singer today does justice to their history. Each lived in an isolated and remote world. She has a famous grave and he does not. In death he is surrounded by family, whereas she is surrounded by stars and the well-remembered. Thinking of

these two lovers, and remembering the most venerable pair of lovers in Père-Lachaise, we can say that neither in life nor in death did Marcel and Edith resemble Abelard and Heloise, well-matched, and one of the most significant power couples in history.

(Sources below.)

February 2025

Sources

Berteaut, Simone. Piaf. 1969. New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

Bosc, Adrien. Constellation: A Novel Based on True Events. 2014. USA: Other Press, 2016

Cerdan, Marcel. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcel_Cerdan

——- http://www.marcelcerdan.com/ImagesFamille/Famille323.jpg

Crosland, Margaret. A Cry from the Heart: The Biography of Edith Piaf. London: Arcadia Books, 1985.

Flight Safety. https://asn.flightsafety.org/asndb/336300

Grimault, Dominique, and Patrick Mahé. Piaf and Cerdan: A Hymn to Love. Trans. Barbara Mitchell. London: W. H. Allen, 1984.

La Vie en Rose (film). 2007. Directed and written by Olivier Dahan.

Leibovitz, Liel. “Edith Piaf’s Deadly Longing.” The Wall Street Journal. May 27, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/edith-piafs-deadly-longing-1464376872