Of the nine movies made by Katharine Hepburn (1907-2003) and Spencer Tracy (1900-67), Adam’s Rib is regarded as the best. The1949 show poster presents the film as an answer to a question: “Who wears the pants in your family?”

Even if you don’t know the stars’ histories, you can’t watch the film without suspecting that there is more to the exchanges between Adam (Tracy) and Amanda (Hepburn) than meets eye or ear. By the time the film was made, the stars were an established couple; their affair lasted some 26 years. The screenplay was written by Ruth Gordon (1896-1985) and Garson Kanin (1912-99), who were married. No doubt their own relationship, and their friendship with the stars, helped to shape the highly-praised screenplay, splendid testimony to the literate standards that Hollywood once reached—wit, edge, depth. The director was the famously literary George Cukor (Little Women, Born Yesterday, My Fair Lady).

Adam’s Rib treats an attempted-murder trial as comedy and weighs the traditions of the legal system against women’s rights. A landmark example of mid-century Hollywood feminism, the film presents Hepburn at her combative and ironic best. Her performance reminded me of a much earlier champion of women, Alison, the Wife of Bath, the most famous pilgrim in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (c. 1390).

Part of the fun, in both cases, is that events and their consequences are somewhat ad hoc, or seat-of-the-pants, loosely coherent, as is often the case in comedy that is meant to be thoughtful but not too serious. This is a kind of feminism that is able to joke at its own expense, a grace that has disappeared.

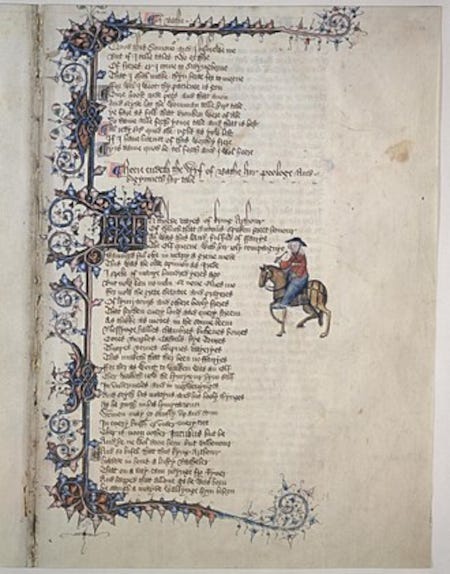

The Wife of Bath and the beginning of her Prologue. Ellesmere Manscript, c. 1400

The Wife of Bath details “the woe that is in marriage,” telling the pilgrims about each of her five husbands and how she fought them. Wearing the pants (so to speak) is a problem for her and her husbands, just as it is for Amanda and Adam. Both the Wife’s account and Adam’s Rib present violence against women, and violence by women, as part of the battle of the sexes. The Wife reports that Jankyn, her fifth and last husband, beat her. She makes no reference to Adam’s rib but does talk about her own. She still feels Jankyn’s blows, she says, “on my ribbes al by rewe” (on my ribs, in a row; prologue, l. 506).

Generations of medievalists have busied themselves trying to decide how much credit Chaucer should get for creating the Wife’s feminist views. At one time he was celebrated as a feminist, but scholars today are much more discriminating when handing out plaudits to white men. We might, in turn, ask how much credit Gordon, Kanin, and Cukor should get for their bold version of the battle of the sexes. How feminist is Adam’s Rib? How seriously does it take violence by women?

In the film’s first scene, Doris Attinger, a much put-upon housewife, follows her husband from his office to the apartment of his mistress. She has just bought a gun. She leafs through the instruction manual just before she knocks on the door of the apartment where he and his mistress are meeting. Once inside, she fires the pistol wildly and ineptly. Her husband is wounded but he survives. Doris is arrested and quickly put on trial.

Doris is played by Judy Holliday. She too has a relevant off-screen history. Holliday had starred in Born Yesterday on Broadway. She lacked screen experience and was not in line for the lead in the film based on the play. Hepburn and Tracy worked to get her hired for Adam’s Rib. The movie served as her screen test (she took another, also a great success). Then, with Adam’s Rib and its stars backing her, she was given the lead in Born Yesterday, for which she won the Academy Award for Best Actress. It was only

Judy Holliday (1921-1965)

her third film credit. She beat out (incredibly) a string of veterans: Gloria Swanson (Sunset Boulevard), Bette Davis and Anne Baxter (both in All About Eve), and Eleanore Parker (Caged). Holliday also won a Golden Globe for Born Yesterday.

Doris’s arrest makes headlines in the next day’s newspapers, which the maid brings to Adam and Amada along with their breakfast. When Amanda reads that a housewife tried to kill her unfaithful husband, she says, “Serves him right.” Adam criticizes Amanda’s contempt for the law. All subsequent references to the shooting reveal the same division between women and men. Taking away the breakfast things, the maid sees the headline and smiles. Later, when Doris gets to work, she finds that her secretary shares her view that the bum only got what he deserved.

This being a mid-century film, the point is not to prove that women are better than men, which would be the point today, but equal to men. Hepburn establishes her feminist credentials in an early scene with Tracy, set in the convertible in which she is taking him to work. As she talks about a woman’s right to treated the same as a man, she swerves into another lane awkwardly, prompting an angry cabbie to denounce women drivers. There are two messages here, one supporting Amanda’s sensible theories, another raising questions about her anything-goes driving.

When Adam gets to the office, he learns that he is to prosecute the case against Doris. The other attorneys consider it a “slam dunk,” but Adam knows there is trouble ahead. He tells Amanda about the assignment on the phone, saying, “The boss wants a quick conviction . . . and l'm the guy who can get it for him.” The men are now lined up against the women.

Amanda fumes. For her this “quick conviction” business is the straw that breaks the “female camel’s back.” She decides to defend Doris and goes to the jail to interview her. Doris reports, rather wearily, that she has been married nine years, four months, and twelve days. Her husband often stays out all night. He has hit her and once he broke a tooth. “I couldn't help myself,” she says of the shooting. Amanda subtly coaches Doris to prepare for her courtroom testimony. Doris will learn to say that her motive was not anger but a desire to keep her home and her family together. In fact, however, Doris admits that her target was the other woman.

That evening Adam and Amada are entertaining; the dinner table looks splendid. As the guests, including judges, sweep in, Amanda announces that she is defending Doris. Hearing this, Adam drops a tray of drinks. Later, in their bedroom, they argue furiously over her decision. He calls her “Pinkie” and she calls him “Pinky.” They are female and male versions of the law, it seems, but the difference between them will soon outgrow -y versus -ie.

Adam believes that Amanda should defer to his wishes out of respect for the law. The script cleverly uses Adam to represent the law as if it were he himself, as if it were male and naturally favoring men’s point of view. Amanda’s mission, her cause, to is undo that assumption. She wants to “dramatize an injustice,” she says, evoking the success of the Boston Tea Party. In other words, she will make a performance of her opposition to injustice, and she quickly does that.

The film’s version of the relationship between gender and violence is complex, mixing broad humor with serious questions about rights and traditions, attempted murder with amusing mayhem.

Attempted murder is only one of the film’s representations of violence, and in some ways it is the least important. Other violence takes place between the couples and tells us more about the movie’s feminist investment. Questioned by Amada both privately and in court, Doris testifies that her husband abused her. When he is on the witness stand, her husband, questioned by Adam, testifies that Doris knocked him down, threatened him, and even split his lip when he was sleeping (scene 16). None of this is challenged by Amada. This pair of accusations is a version of the Pinkie (she says) vesus Pinky (he says) structure of the Amanda-Adam marriage.

Violence between Adam and Amanda unfolds in two episodes. After their first day in court, Adam gives Amanda a massage. They talk about the day and their positions as opposing counsels. Suddenly he slaps her bottom, hard (scene 19). She is shocked and furious. “You meant it,” she shouts—i.e., it was not an act. She denounces his “instinctive masculine brutality” and then says, “You’re really sore at me.” He admits that she is right. What has upset him? It’s not Kitt, the frivolous and flirty man across the hall who wants to have an affair with Amanda. Adam, a barometer of masculinity, thinks Kitt, a pianist, is on his way to becoming a woman and is half-way there; scene 14. What angers Adam is the “fun” Amada is having in the courtroom, where she is “shaking the law by the tail.” We should read this as shaking men by the tail, i.e., shaking him.

Offended, she weeps. “The old juice,” he scoffs, “a few female tears.” Then he realizes she is really upset and tries to apologize and sympathize. When he gets close, she kicks him. That’s the perfect Adam’s Rib exchange, Pinkie versus Pinky, tit for tat. There is little that is funny about the scene, and that is so because of the labile aspect of Hepburn performance. Her extended weeping is pained and pathetic. But, once or twice, it nears parody. We cannot laugh at the fact that she is humiliated by his slap. But we are expeced to enjoy her revenge, an echo of Doris’ revenge.

This scene parallels the Wife of Bath’s famous battle with Jankyn. “He hadde me bet on every bon,” she says (“he beat me on every bone. l. 511). He is a scholar (a clerk, educated), and he loves to read to her from a book about wicked wives. Fed up with these lessons, one day she tears a leaf from the book. He hits her, and she becomes deaf. She immediately knocks him into the fireplace, and he gets up to hit her. When she falls, she says she is dying. He kneels and apologizes. Then she strikes him again (ll. 792-809).

The Wife enrages Jankyn by tearing a page out of one of his books. He hits her; she dramatizes the abuse and gets him to apologize. Likewise, Amanda enrages Adam by shredding—having “fun” with—his “book,” the law, in court. They exchange violent acts, just as do Jankyn and the Wife.

The Wife’s autobiography is merely a preface to her tale, an Arthurian story which teaches that even a rapist (in this case, a young knight) can earn marital bliss if the violent man submits to the advice of a disagreeable woman with hidden magical power (she is often described as a “loathly lady”). The contradictions within the Wife’s version of her history disappear in the mix of humor and candor that distinguishes her prologue and that are all but hidden by the neat logic of her tale.

Adam’s Rib uses humor and wit to resolve the tension of violence. In her summation, Amada asks the jury to imagine Doris as a man (and to imagine her husband as a woman).

Doris at the defense table, above, and as she might appear as a man.

These shots cleverly put the viewer in the jury’s position. The jury finds Doris not guilty. After the verdict is reached, the battling lawyers return home. He is visibly angry. She asks him to be reasonable and to talk to her, confirming the still-common feminist claim that men are not communicative. He does indeed have more to say. He likes two sexes and he denounces the “new woman,” mocking the cause of women’s rights. He hates her contempt for the law. Marriage is the law, he says, a contract. He gathers his hat and coat and heads for the door, hinting that their marriage is over.

This argument between Adam and Amanda is a deep exploration of the meaning of law and contract (scene 22). When Amanda persists in her “talk to me” approach, Adam declares that he has said everything he meant to say. He accuses her of behaving like a he-woman. Unexpectedly, she does the violent, “masculine” or he-man thing and shoves him into the door. He is wide-eyed with surprise, and I had the momentary feeling that the scene had gone beyond what either actor had imagined, that it had tapped some extra—some outside—energy and feeling.

Adam up against it

He turns to go. Relentlessly in charge, even at this point she reaches for conrol, forbidding him to slam the door, which he does, setting off a chain reaction of falling pictures and lamps. This is a comic touch, similar to the earlier moment when they bang a swinging kitchen door into each other. However, the violence is no longer funny. The lamp, pictures, and plants that are falling in chain reaction stand for traditions that are giving way, losing their place: the ordinary stuff of life thrown into disarray, destroyed.

Later, in the bedroom, Adam and Amanda talk about their feelings. He shows her that he can weep at will and demonstrates how he would handle a “tough scene” between the two of them. He produces and wipes away tears, then jokes about his performance. He has shown that men can play tricks too. She agrees and insists that he has now proved that she has been right all along: there is no difference between men and women in this and other regards. Slyly he objects. Sitting on the bed, she agrees that there may be a “small” difference.

Delighted with this concession, Adam shouts “Hooray for that little difference.” He jumps up on the bed and pulls the curtains around them. The retreat to a bed closed off with curtains—a retreat to sex—is the end of the film and also the end of the argument. Adam’s Rib turns a movie about violent marital disagreement into an exploration of theater, acting, and performance. Ad hoc, seat-of-the-pants nods and winks leave us wondering about connections between the lives imitated by Katharine and Spenser and the lives they lived.

September 2024

At what point must we face the war between the sexes honestly? In a work of fiction the writer(s), actors, and audience can portray and/or interpret whatever one wishes. To some extent the same can be said of the real world. Royalty, indeed any official, is often treated as divinely appointed, and submission to them is widely seen as having been decreed.

But in actuality, no one has the right to command, and no one has the obligation to obey the commands. Throughout history there have been rulers who abused those over whom they ruled and those who have been willing to sacrifice their freedom, health, and lives rather than obey. Other rulers and officials have ruled benevolently and who have been obeyed willingly.

The same can be said of married couples. Not all husband are abusers, nor do all wives feel put upon. Most marriages at least begin happily. Some even grow more happy. That cannot happen nor can it remain when one or both of them tries to lord it over the other. In Paul's words in Ephesians, submit yourselves to each other. That applies in marriages--and in politics.

The meaning of public service has been nearly lost. Hardly anyone is willing to submit themselves to anyone. Instead we are always looking for opportunities to take advantage.

Class and the sparkling intellect, wit and humor of 'Adam's Rib' and many of the old classics has long made the older genre favorite. The Classics are also a measure of the poverty of talent, skill, grace and class; not to mention wit and humor today. Movies today simply could never leave out 'f-Bombs' or worse.

The depth of language usage through both the body, facial experssions and words placed a sense of reality to the films once brought to the public and moderation was the average in presenting social issues.

THANK-YOU FOR THIS FINE ARTICLE DEFINING YOU A FINE 'CRITIC AND AUTHOR,' YOURSELF.