Boxing and race: heroes need not apply

In the 1930s, boxing star Joe Louis and track star Jesse Owens could make history, but not money.

Donald McRae’s Heroes without a Country: America’s Betrayal of Joe Louis and Jesse Owens (2002) tells two sad stories that sports historians too easily forget.

The track sensation Jesse Owens and the great heavyweight Joe Louis were the first black athletic heroes of modern America. They were “without a country” because the nation was unwilling to recognize either as a free man, say nothing of seeing either as a man who had exceeded the masculine standards to which most men were held. Their heroic masculinity emerges not only in their talent but in their ability to withstand life-long scorn and discrimination in the land they called home. Both Owens and Louis were sons of Alabama sharecroppers and grandsons of slaves. Born in 1913, Owens died in 1980. Louis, born in 1914, died in 1981, also 66 years old.

The nation was not prepared to hail these men, or even to recognize what they had accomplished. Organizations and individuals, from the Amateur Athletic Union and its leadership to the IRS, undermined the achievements of Louis and Owens and devalued their success. The men’s greatness as men could be diminished, but it could not be erased. Two heartening and exciting chapters describe the young athletes’ first great moments.

For Owens it was at Ann Arbor on May 25, 1935, when he set three world records and tied a fourth in 45 minutes of running and jumping (ch. 2). The first great moment for Louis came just a month later, June 25, 1935, when he demolished Primo Carnera before a crowd of 60,000 in Yankee Stadium, a group said to include 15,000 black ticket-holders (ch. 3).

Their victories were loaded with political significance, good in some ways, bad in others. Boxing, track, and other individual sports almost always make it absolutely clear who wins. If the winner in the ring or on the track does not measure up to the public’s idea of a winner (that is, as a man who is like the men they know, only better), he will, in significant ways, still be seen as a loser.

During the lifetimes of Owens and Louis, heroic achievements did not outweigh color. Despite their celebrity, neither Louis nor Owens was able to walk into restaurants and expect to be served. Hotels in big cities and small refused to accommodate them. En route to a track meet, Owens and other black runners were nearly forced off a train that, during a storm, had been rerouted into Kansas, where blacks were not allowed on certain routes.

On many scales of masculinity, either men would have been at the high end, if not on top, outperforming the best in his field. Their color, however, trumped their masculinity, except when it could be used to demonize them as sexually threatening.

Louis (born Joe Louis Barrow) was the more successful. He would eventually be paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for big fights when Owens was pumping gas to support his family. The disparity between their achievements and their social standing—their human standing—is painful to behold.

Joe Louis

Louis fought the Italian heavyweight Carnera when Mussolini was coming to power. Louis’s victory brought him national attention for that reason as well as for his race. A few months later, Louis defeated Max Baer for the heavyweight title, another fight portrayed as a racial contest, as were most of Louis’s fights. In 1937 he took the heavyweight title from James Braddock in Chicago (Louis at right).

Louis boxed in the shadow of Jack Johnson (1878-1946, below), the first black heavyweight champion and a man whose success with white women predictably infuriated the boxing public (by Johnson’s design, it seems).

McRae points out that both Louis and his coach were warned, when they won, to keep their joy in check lest they provoke a race riot. Given Louis’s lifetime record of 66 wins and three losses, with 52 knock-outs, that meant a lot of suppressed smiles.

In 1936, in their first match, Louis lost to Max Schmeling, Germany’s great white hope, even though Louis was a ten-to-one favorite. He lost on Juneteenth, black Emancipation Day, making the defeat especially bitter. Many in the U.S. were rooting for the German and celebrated his victory. In their rematch in 1938 Louis knocked out Schmeling in the first round. Louis went on to defend his title 25 times, still a record. He reigned as champion longer than any boxer ever had, in any weight class. He managed money poorly and died poor and drug-addicted. Schmeling was one of his pall bearers and helped to cover the expenses of Louis’s funeral. After his death, Louis was said to have done more for black people in America than anyone since Abraham Lincoln.

Louis’s masculinity extended from the ring to service to his nation. Louis was an extraordinary patriot. He donated winnings from his victory over Max Baer to the Navy Relief Fund for victims of Pearl Harbor. His power became especially evident during his time in the U.S. Army. At the peak of his fame, Louis enlisted in a black regiment in 1942. His enlistment was much-publicized and his patriotic public appearances were carefully coached. At a fund-raising dinner he was supposed to say, “We will win because God is on our side.” Instead he said, “We’ll win because we are on God’s side” (p. 231). The line was a huge success, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a telegram to thank Louis for it.

In a masterstroke of cynicism and hypocrisy, the Army, which strictly segregated blacks, placed the boxer’s picture and the famous line on recruiting posters. No fighter since Jack Johnson had received so much attention, and only Muhammad Ali would eclipse Louis in the decades ahead. (See Kasia Boddy’s Boxing: A Cultural History for an illustrated account of Louis’s impact.)

Jesse Owens

Even though he too came from poor people, Owens seemed middle class because he attended Ohio State University for a while and because he excelled at a favored university sport, track. He was also a good public speaker, articulate and savvy. When his competitive career was cut short by the people who should have been encouraging and supporting him, Owens proved to be practical, hardworking, and humble.

Owens achieved enduring fame with his astonishing performance at the University of Michigan in 1935. When he arrived in Berlin for the Olympics a year later, he was greeted by thousands of people chanting his name (pp. 140-41). He was “the most famous international athlete in Berlin,” McRae writes. He would never have received such a welcome anywhere in the U.S. It was said that those Germans who knew two words of English knew “Jessie Owens,” and those who knew four knew “Jessie Owens, Joe Louis” (p. 164).

Owens (above, wearing laurel wreath, with three medals) triumphed in front of Hitler and his lieutenants at Berlin, winning four gold medals. But that was the end of his career as an athlete in track competition. The Amateur Athletic Union leadership saw to that. After his Olympic triumph he was banned from further competition. He was cut off from the mainstay of his fame and his masculine dominance.

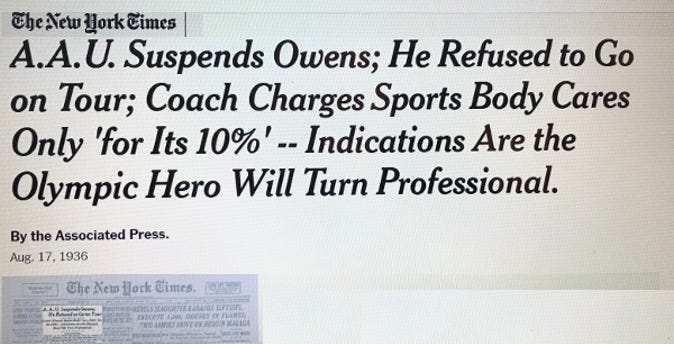

What happened? The AAU leaders, Avery Brundage and Dan Ferris, had organized a six-week series of meets to follow Berlin, without telling the athletes until they were already in Germany. The athletes were poorly looked after as they were shuttled around Europe for these meets, which profited both the AAU and Brundage and Ferris, men who were the faces of “the greed and hypocrisy of the national union” (p. 166). Owens and his manager made most of these added meets but refused to go on one leg of the trip. Owens was disbarred for violating his contract. The world was shocked; the story made the front page of the New York Times on Aug. 17, 1936.

Owens was forced to turn pro and thus could no longer participate in amateur races. Brundage went on to run the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. He was known as “Slavery Avery” for his anti-black racism and his anti-Semitism. Owen was one of his first victims. After Berlin, Brundage had a long and well-funded career of discrimination ahead of him at the IOC. Owens’ future was not so bright.

If you look at the entry for Owens on the official site of the US Olympic Committee today, you find nothing about this. Rather, you read about how wonderful Owens was and how unfortunate it was that World War II kept him from competing again. “War denied Owens the chance to extend his Olympic legend and garner further medals – who knows what he might have achieved at a 1940 or 1944 Games” (https://olympics.com/en/athletes/jesse-owens).

In fact, in was Brundage and the AAU that denied Owens a future in track. After Berlin he had been declared a pro and could not have run in other Olympic races, or in any other official track event. His banishment was not lifted until 1984, after his death (which was in 1980). In 1984 the AAU vacated the suspension and acknowledged that Owens had not been allowed due process in the matter. In 1986 the rule prohibiting professional participation in most Olympic competitions was loosened.

One of Owens’ medals sold in 2021 for more than $1,000,000. Other medals have been auctioned since.

Owens knew that had been snubbed. While some focused on Hitler’s views of the black star, Owens himself saw indifference closer to home. President Roosevelt, hero to millions of traditional Democrats even today, did not acknowledge Owens’ Olympic victories or have him come to the white House. “Hitler didn’t snub me,” Owens said in 1936; “it was our president who snubbed me. . . . The president didn’t even send me a telegram.” Owens might have defeated racism on the world stage, but could not escape it at home, even at the highest levels (quoted from the Jefferson City Post-Tribune Oct. 16, 1936; see McRae, p. 174, and The White House Historical Association’s essay at https://www.whitehousehistory.org/running-against-the-world).

After Berlin, Owens never ran another amateur race. Instead, so long as he could run, he ran in circus-like exhibitions against animals and machines, forced into it because he could not compete otherwise. The dehumanizing side of the exhibitions he participated it was one more price he paid for being a black star. He raced against horses for five years (1938-1943), worked as a manager for Ford Motor Company, and then was part of a sideshow on tour with the Harlem Globetrotters (up to 1949).

His redemption, such as it was, came in 1950, just 15 years after his sudden fame, when he won an Associated Press poll and was named the greatest athlete of the last 50 years (p. 251), another golden a measure of his manhood. At the time he was sales director for a clothing line (not his own) and was marketing a laundry business in Chicago.

International views

Louis’s victory over Schmeling and Owens’ victories in Berlin were widely seen as proof of America’s superiority over German bigotry. But Germans were not impressed by American denunciations of German racism. They pointed to America’s long history of slavery and discrimination and asked who Americans were to accuse others of racism. Owens gave an interview expressing his belief that the U.S. should avoid Germany if the country discriminated against minorities. His coach, Larry Snyder, was angry when he heard about this statement, and said, “Why should we oppose Germany for doing something we do right here at home?” (p. 131), a remark that touches the depths of truth and hypocrisy at the same time.

As Louis realized during his Army years, however, the world was changing, and his fame was part of the reason. Louis’s enlistment was celebrated and seen as a great opportunity to boost support for the war, and his enlistment was watched over by powerful figures in Washington. Truman Gibson, a black lawyer who worked in the War Department for the Head of Negro Affairs, arranged for Louis to be stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas. There he met other black athletes who had enlisted, including Jackie Robinson, who, in 1945, because the first black to play major league baseball, and Sugar Ray Robinson. These two men who fought back, literally, against racial insults thrown at them.

Robinson was “a formidable boxer and college football player,” McRae notes, and “also played a little baseball” (p. 235). Robinson did not play baseball at Fort Riley, however, because the baseball team was white. But thanks to Louis’s Washington contacts, Robinson and other blacks were for the first time admitted to Officer Candidate School at Fort Riley. Until Louis, a black man could not complete to become an officer; blacks could not compete on that highly visible and important scale of masculinity.

When a white officer disparaged a black soldier with the then-universal epithet, Robinson confronted him, telling him that he should not speak to a soldier in the U.S. Army in those terms. When the officer applied the same term to Robinson himself, “he broke almost every tooth in the white man’s head.” Amazingly, thanks again to Louis’s connection to Gibson, Robinson was not punished. Later, at another camp, an Army bus driver told Robinson to get to the back of the bus and pulled a gun on him. Robinson grabbed the pistol and smashed it into the driver’s face. McRae understandably relishes these episodes. I would not consider them as heroic masculinity at its best, but the episodes undeniably create a deep-seated sense of satisfaction.

Louis met another Robinson destined for fame, Sugar Ray Robinson (whose given name was Walker Smith, Jr.). Sent by an MP in a camp in Alabama from the white to the black bus station on the base, Louis and Robinson refused to go. Two other MPs joined the fight that broke out until one of them recognized Louis. The MPs were reprimanded because Louis threatened to call the White House.

Louis told Gibson about segregated facilities on army camps across the U.S. Gibson reported the fact to the Under Secretary of War, but nobody believed it. Then the Under Secretary called Fort Bragg and found that it was true. The Army banned segregation on bases across the country in 1943 (p. 238), but, as the Army notes today, it took an executive order from President Truman, in 1948, to make progress. There was resistance all around, and it was years before segregated facilities disappeared in the armed forces.

Louis was connected to the heavyweight world that came after he had peaked. He was allied with Sonny Liston when Liston lost the title to Muhammad Ali. Louis had made a fortune in the ring, but, like so many boxers with no financial acumen, he lost almost all of his wealth, or gave it away, and died poor. Owens did better, giving up racing horses for a living and pursuing a cleaning business. Louis died of a heart attack, sick and addicted. Owens, who had become a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer. Louis is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Owens in a cemetery on Chicago’s south side.

Louis and Owens each had a big life, filled with fame and failure. McRae does a fine job of pulling their complex histories together. He draws on extensive resources, ranging from interviews with those who knew these athletes, to taped interviews, television programs, and thousands of newspaper accounts. McRae describes his sources but does not document them. More frustrating for the reader with an interest in boxing history is the lack of an index, a tool very useful in tracing connections among boxers, trainers, and trends in the sport in a long book with a sprawling structure.

That said, however, McRae’s book packs a punch for anybody with an interest in sports history and, and for anybody wary of the tendency of historians to celebrate the golden moments in these men’s careers and to ignore the grime that surrounded their triumphs.