A recent conversation between David Shackleton and Janice Fiamengo focused on the dominance of feminism and the difficulty of correcting its prejudices. Fiamengo wondered if there were “anything effective that we can do in advocacy against it.” Their discussion moved beyond moral polarization to larger questions of how, when, and even if we can defend our values and beliefs when they are attacked. Defense and offence: that’s boxing, a sport that makes polarization starkly plain. Boxers understand a fair fight, but today how many people do?

Shackleton is an advocate of non-confrontation. He sees polarization as “a form of psychological regression” and as “an addictive immaturity in which we can do great harm without realizing it.” He recommends that we approach the opposition “with respect” rather than with “a conviction of moral superiority.” Fiamengo observes that such all-purpose empathy would require Christ-like generosity.

In advocating empathy and compassion, Shackleton offers contrasting examples. First is the television detective Columbo (Peter Falk, below), who was, he says, “motivated by a vision of a good and caring society that he is a part of and seeks to support rather than by black and white moral judgments.” Columbo is part of a world “that we have been progressively losing since the 1960s.”

For “black and white moral judgments,” Shackleton points to Jack Reacher (Alan Ritchson, above), the hero of Lee Child’s many novels (all of which Shackleton has read) and the center of an exceptionally successful Netflix series. Rob Long, a television producer and media critic, dismisses Reacher as a “good psychopath,” a “morally upright” hero with a “shadowy paramilitary” background who goes after the bad guys (Commentary, April 2024). The second season of Reacher, Long notes, “became Prime’s top show within six days of its release.”

Columbo on one hand, Reacher on the other: two ways of fighting, one with kid gloves, one with bare knuckles. Is there a model that stands between them? I see that figure in General (and former President) Dwight D. Eisenhower, a man of tremendous martial accomplishments whose life and history nonetheless model the some of the behavior Shackleton admires. Part of my admiration for Ike is that he pulled on boxing gloves and did some boxing at West Point, where he was a cadet of head-turning handsomeness. Later on, boxing was one his “favorite metaphors for politics” (David Eisenhower, Going Home to Glory, p. 88).

Eisenhower at West Point, 1915

With Rocky Marciano in the 1950s

Reacher is tough, a man of his word. Columbo, at his toughest, is a man of many words. “I must say I found you disappointing; I mean your incompetence. You left enough clues to sink a ship. And for a man of your intelligence, you got caught in a lot of stupid lies” (“How to Dial a Murder”). Stupid lies, incompetence, disappointing? Definitely black and white moral judgments. Reacher might have expressed the same sentiments but would have made his point succinctly.

The viewing public has an appetite for Reacher. He responds to the current political landscape, with its woke rhetoric, progressive dogma, and routine disparagement of men. In Reacher people see something that they know society needs: decisive action that restrains evil and gives ordinary people a chance to live the way they want. Good and caring societies come with a price. They can be put at risk if nobody counters bad actors.

However caring, Columbo has his drawbacks. Fans must overlook put-downs of his wife and other women. Reacher is unfailingly chivalrous (of course, to the woke, this is criminal) and has a history of training and serving with skilled women warriors. As Fiamengo points out, Reacher is sometimes shamed by women for not being feminist. His chivalry undercuts female autonomy and is read by some viewers as demeaning. But that is not always the case. After one particularly skilled and brutal woman demolishes her opponent, Reacher admires her “nice moves.” She acknowledges that she learned them from him, but it’s clear that she did not need his help to do what she had to do.

Reacher is forceful; Columbo is not. Reacher never uses force for its own sake, although few would accuse him of moral superiority, a defect Reacher can spot in those he is trying to help. When a cautious and legalistic detective conducts an unauthorized search, Reacher affects surprise, amused that the man departed from his usual professional fastidiousness. “At least I don’t kill people,” the lawman says churlishly. “You’ll come around,” Reacher replies.

Shackleton condemns moral superiority as if it did not exist, or as if differences in the qualities of human behavior were insignificant. He urges respect for the opposition, not confrontation. Fiamengo deftly rebuts his point. “But do we adopt the empathy no matter what, in a Christ-like manner? ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do’?” She continues, with the clarity and spirit that explain why her fans love her:

If you play for a team that passes the ball to the other side as often as it passes to team members, while the other team never passes to your team, then even with greater skill and merit on your own team, you’re going to lose game after game. That’s what I fear: that in aiming at decency when the other side is not decent, we are in the process of losing everything. The harm is then, of course, not only to us but to generations unborn in that we allow the takeover of the culture by people who hate them and will harm them.

Fiamengo offers a brilliant defense of going to war—not just to right a present wrong, but also to preserve justice for the societies yet to come. Shackleton has no answer. He acknowledges that she asks good questions and admits that he lacks what he calls a “generalizable solution for how to combat the woke, the feminist.” Yet he returns to his “conviction, a faith I guess, that it is possible, and preferable, to oppose evil from a place of love, of empathy and respect.” He wants to approach evil decently. But, as Fiamengo says, if only one side is decent, decency is a lost cause.

Empathy and love, by Shackleton’s own standard, themselves do nothing to preserve values we cherish, or even to preserve our own selves. Would Shackleton have advised the Sioux Indians to empathize with the settlers who were killing them, destroying their livelihood, and taking their land? Yes. What would that have done but ensured the Sioux of their own extinction? Nothing. Should Ukrainians brew tea for the Russians? Should Israel welcome a Palestinian government? Yes to both. Doing the decent thing can backfire.

Shackleton confuses sacrifice, which is the price of preserving what you want to keep holy, what you cherish, with self-sacrifice, which is the decision to abandon your fight and take on a symbolic role, to become a statement—that is, a martyr. He is not the first to believe that voluntary martyrdom—he calls for nothing less—is the surest road to sanctity, or, in his case, as an observer of other peoples’ pain, to guilt-free goodness, the woke paradise.

Respect is a different matter. Respect does not require that I believe the opposition’s case to be superior to mine. If I thought so, what reason would I have to for guarding my beliefs? Respect does, necessarily, require due regard. I do not admire poisonous snakes; I have due regard for them, however. Likewise, I do not admire intersectional feminists, but I also have due regard for them. You show due regard by sizing up your opponents. Reacher never underestimates the power or the cunning of his adversaries. On the contrary, like Jesus before his execution, he counts on them to underestimate him.

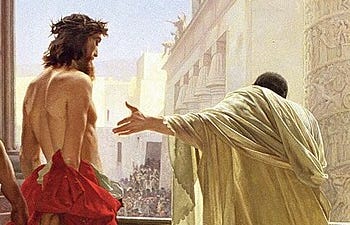

I read the exchange between Fiamengo and Shackleton on Good Friday morning. In church that afternoon I listened to the Passion according to St. John. It seemed to me that the approach Jesus takes to conflict could, as Fiamengo suggests, be the model for Shackleton’s view. As he stands before the Jews and Pilate, Jesus does not make accusations or regress to simplistic views. He is his own advocate.

That said, there is more to this scene than the lamb’s silent wait for sacrifice. Both politically and psychologically, Jesus is astute. He is adept at pointing to inconsistency. He exposes his adversaries, a hint of his inner Reacher. He succumbs to them, but he knows that their damnation hinges on his death, a transaction no one else could replicate.

The conflict in the Gospel is not between Jesus and the Jews, or between Jesus and Pilate, but between Pilate and the Jews (John 18:28-19:42). Jesus does not misrepresent or antagonize either party. Free of reproach, he states facts when he speaks to Pilate. He asks reasonable questions. He also exploits the value of silence.

Ecce homo, Antonio Ciseri (1850, public domain; Uffizi, Florence)

When Pilate asks the Jews what Jesus has done wrong, their reply is circular. Jesus is a criminal because they say that he is. Otherwise they would not have brought him to Pilate (18:30). Pilate tells them to judge Jesus by their laws. Because they cannot execute criminals, they demur (18:31). Jesus is a threat to them, and he has to die.

Pilate observes a different law. Asked by Pilate who he is, Jesus says that he has come “to testify to the truth.” He refrains from answering Pilate’s famous question, “What is truth?” (18:37). Pilate interrogates Jesus but can find “no guilt in him” (18:38). Since the Jews do not want Jesus released, Pilate punishes him by having him scourged (19:1). But that is not enough. The Jews want Jesus crucified. Having declared Jesus innocent, however, Pilate resists this demand.

Christ as Man of Sorrows, Donauwörth, Germany (2006)

When Pilate asks, “Are you king of the Jews?” Jesus poses a question himself: “Do you say this on your own, or have others told you about me?” (18:34). Pilate points out that the Jews have handed Jesus over and asks him, “What have you done?” Jesus’s answer is enigmatic. “My kingdom does not belong to this world.” He implies that he is no threat to Pilate or “this world.” But Jesus does not point out that he is about to change that world. His death will alter history. Time will, in time, become BC / AD or, as we now say, BCE / CE. History, in several senses, is about to be remade.

Christ adds that if his kingdom were a worldly kingdom, his followers would have fought to protect him. Pilate asks, “Then are you a king?” Jesus responds with a mirrored statement: “You say that I am a king” (18:36-37). It is worth noting the slippage between Pilate’s question and Jesus’s response, which rephrases the question as Pilate’s own belief. “Then are you a king?” becomes “You say that I am a king.” Pilate, however, said no such thing.

Pilate interrogates Jesus a second time and asks where he has come from. Jesus does not answer. Pressed for a reply, Jesus merely tells Pilate that all power comes from above (19:9-11). Pilate might draw his own conclusions from this heavy hint, but instead he seems confused and hesitant, perhaps surprised by a confident and articulate suspect who is given to speaking in riddles.

Sensing Pilate’s hesitancy, the Jews up the ante, insisting that Jesus is not just their enemy (Pilate is not impressed by this claim) but also the enemy of Caesar, the one true king. If he releases Jesus, they warn, Pilate will no longer be regarded as Caesar’s friend. Afraid of being seen as disloyal, Pilate hands Jesus to the Jews to be crucified by Roman soldiers (19:12-16).

Jesus now becomes the scapegoat, the sacrificial victim without the power to defend himself. His death will bring brief peace to the parties that war around him. But it will not turn out to be a Columbo-like “good and caring society.” For the moment, the Jews are satisfied and Pilate remains in good standing with his boss. In about 35 years, however, the Romans will make war on the Jews and their temple will be destroyed.

Detail from La distruzione del tempio di Gerusalemme (Francesco Hayez, 1867, Accademia Gallery, Venice).

Jesus, then, is not, after all, a paradigm for Shackleton’s view of conflict. Jesus is perceptive but not empathetic. He understands and respects the motives of his enemies. He has due regard for them, that is to say, but he cannot share their convictions. His dying words call for their forgiveness not because they are innocent but because they are ignorant. Could one say that Jesus is motivated by “a vision of a good and caring society that he is a part of and seeks to support rather than by black and white moral judgments”? Hardly. He has a vision of “a good and caring society,” to be sure, but, as history will show, it will be open to Jews or Romans only at great cost. They must choose to be in or out, up or down, with him or against him. There is nothing in between.

The Jews and Pilate are adversarial. The former see conflict in black and white; they are enraged and abusive. Pilate is evasive and legalistic. In between these forces, Jesus is able to ”advocate in the world, with respect for those who oppose [him].” He says nothing about the Jews, and when talking to Pilate, he mirrors Pilate’s own language, which obscures his opinion of what Pilate says but also, in a subtle way, challenges him. Jesus retains the upper hand, even as he proceeds to his death.

Before being brought to Pilate, Jesus deftly handled the Jewish temple police and Roman soldiers, not resisting them and asking twice whom they sought to arrest (John 18:4, 7). Then, in custody, when quizzed by the high priest about his beliefs, Jesus did not respond as an adversary. He pointed out that he never taught in secret and then posed a question, “Why do you ask me?” Obviously inattentive students, they ought to know what he has been teaching. Struck by an officer for this cheeky response, he asks if he has spoken wrongly. If he has not, he says, “Why do you strike me?” (19: 20, 23). Jesus repeatedly uses questions to respond to aggression. This is not empathy, although it is respect. Showing due regard, a model of confrontation without conflict, these scenes are the mark of a man who is in charge.

Jesus is deferential but determined. His example warns us not to confuse respect with passive acquiescence. Shackleton is asking for active acquiescence, indeed for love, even though he disregards moral superiority. This is where he loses me. For reasons of history, including his demonstration of wisdom, we must assign moral superiority to Jesus. If answered, his questions would show him to be free of blame and wrongdoing. In what sense is he, the incarnation of love and forgiveness, not superior to the leaders of the Jews and the leaders of the Romans? Throughout his long dialogue with Pilate, Jesus quietly and calmly demonstrates his superior status and, I believe, reinforces our conviction of his moral superiority.

Some men, although lacking the credentials Jesus brought to his confrontations, show signs of Shackleton’s philosophy of respect and reasonableness and yet retain the upper hand. My example is Dwight David Eisenhower, who manifested martial virtues that suggest Reacher at work, not Columbo. A man of extraordinary achievements, Eisenhower led two brilliant, pivotal military campaigns (North Africa, 1942; Normandy, 1944), served as president of Columbia University, and ended his career with eight years as President of the United States. His retirement was also productive, overshadowed though it was by the brash start of the presidency of John F. Kennedy, Kennedy’s assassination, the ascent of Lyndon Johnson, and the civil rights battles in the 1960s, which began on Eisenhower’s watch in the 1950s.

In 1958, the middle of his second term, Eisenhower shared with fellow Republicans one of the most valuable lessons about fighting he had learned. It did not come in Africa or Normandy, or at Columbia, one of today’s centers for conflict and confrontation, but earlier, at West Point, in the boxing ring. A member of the West Point Class of 1915, Eisenhower enjoyed boxing. One day he was knocked down by a bigger and more experienced fighter. When “I got up from this blow,” Eisenhower said, “he [the other boxer] looked at me and he said, ‘You smiled.’” Eisenhower “wondered what he meant.”

He soon found out. Knocked down again, he “got up looking rather rueful.” Thereupon his opponent “took his gloves off and threw them in the basket in the corner and said, ‘Well, I'm done boxing with you.’ I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ He said, ‘If you can't smile when you get up from a knockdown, you are never going to lick an opponent.’” Eisenhower had it right the first time. Responding graciously to a setback does not mean you give up. Instead, it should harden your resolve.

The smile is one way of advocating with respect, as Shackleton urges. The boxer who is knocked down does not get up looking pitiable or angry or “rather rueful,” but rather looking like a good sport. His smile means “no hard feelings. I am ready to go again.” That also shows confidence.

Never strident and seldom pointed, Eisenhower loved to fight. As President, he shared with John Foster Dulles, his Secretary of State, the view that “battle is the joy of life.” In a note to himself in 1947, he wrote, “Battles are not won by pessimism” (Eisenhower, Going Home, pp. 19, 51). If not with a smile, battles are won by optimism and confidence. When he was President, Eisenhower based his decisions and actions on his extensive experience of crisis and hardship. His great achievement as president was to balance diplomacy with threats of military action.

He knew when to play his hand. In 1957 Governor Faubus used the Arkansas National Guard to block black students from getting into Central High School in Little Rock. Eisenhower addressed the nation. He denounced extremism and disorder and sent the 101st Airborne Division the Army to make sure the students got in.

The boxing lesson from 1915 stayed with Eisenhower. He knew how to lose gracefully, with a smile. His audience in 1958 had a long-lasting opportunity to test his lesson in winning and losing, for that was a disastrous year for the GOP. The party lost 49 seats in the House, which came under Democratic control. The Democratic majority lasted until the Gingrich revolution of 1994.

In my experience in and out of the ring, boxers do not ordinarily smile under any circumstances. Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion (d. 1946), smiled in the ring. Max Baer, also a heavyweight champion (d. 1959), was a famous joker and wise-cracker and was thought by some to be more entertainer than boxer (see Schaap, Cinderella Man). I never heard a coach tell a boxer that smiling as he got up was part of what made him a winner, although I can see the point. The smile expresses willingness to take the risk of being bested and also determination to continue the match. A good boxer keeps his spirits up and knows the importance of not looking—much less being—overwhelmed or defeated. A good boxer is ready to play his hand.

A smile might be menacing, as Baer’s certainly was, but it also expresses joy and confidence, an understanding that the contest underway is not limited to hostility, abuse, or the speech that boxers today call trash talking. I smile when my coach lands one that I did not see coming. I’ve been tricked, and although I don’t like getting hit, I can’t help but enjoy his success and his skill. When I land a shot, he’ll say “good one,” smile or no smile, showing me respect.

I propose Eisenhower as a leader who respected the enemy, especially when he approached the enemy with an army, whether in Little Rock or Normandy. He directed complex missions that, whether won or lost, would send thousands of men to their deaths against the Germans. He was more serious than he was charming. Kennedy was more charming than he was serious. Who was better qualified to lead the country?

Calls for empathy, respect, and love cast an aura of Gandhi-like sanctity around those who make them. The hard work of challenging error and injustice falls to writers like Fiamengo, Bettina Arndt, and Tom Golden. They expose feminists’ counterfactual claims and feminist hatred of men. Shackleton is safe in his retreat. Feminists and the woke will never challenge him because, to use Fiamengo’s analogy, he is always passing the ball to them. His idea of empathy is to help the opposition advance its cause. The opposition’s idea of compassion is to let him. Given the choices—Reacher or Columbo, Fiamengo or Shackleton—I’ll take Jack and Janice, and, not to forget, Ike and Jesus.

Thanks Allen for an excellent look at the issue of action/empathy. Loved the ideas of Jesus and his skillful use of questions. Especially loved "Jack and Janice"!!. Thanks too for the mention. Much appreciated

There is a time for action, hard, physical action. Knowing when that is and when to use empathy is an important trait for us all. When your child is running into the path of an oncoming car it is time for action. Empathy comes later. Same is true for today's feminism.

A truly wonderful piece here, Allen. I particularly admire your parsing of the Christ story. Though I have very little patience for opinionated folks who are guided by ignorance, I have had some success using the questioning method you describe here. "Why are you so hostile?" "What exactly did I say to upset you to such a degree?" "Do you believe...?"

The main thing that irks me is that folks tend to believe what they want to believe, irregardless of education and information. So I wind up asking myself, why they believe whatever cockamamie crap they believe. And this leaves me feeling exasperated, since there's really nothing they might learn that could change their minds. Why waste my time? But then I'll see someone taking the time to explain critical information, and, by God, it works!

A few months ago, I received an email from someone I thought was a friend. It was a long lecture on the errors of Israel's operations in Gaza. Since I had a lot more knowledge on the subject than he, I wondered what compelled him to lecture me. I wasn't especially polite, but I was respectful and asked if this was a lecture or a conversation. He replied that it was a conversation. So I sent him some resource material and asked him when he'd like to meet to have a conversation. I never heard back from him. As I intuited, it was never a conversation, and he wasn't interested in learning anything. He believed what he believed for his own reasons and that was that.

I'm sure there are ways of getting through to folks who are both passionate and ignorant, but I generally lack those qualities and skills. So my hat's off to those with the talent. It takes all kinds. Maybe Shackleton's way works for him. But I'm not that guy. I'm more likely going to simply declare that I think your ideas are uninformed and that you could use some further education. That's generally taken as an insult. And I figure it ain't my problem. They had to hear it from someone... should have been their teachers. I've noticed that folks who grew up being told they weren't so smart, have more humility than those who were told they were geniuses. Unfortunately, we live in a society in which all our kids are above average. No wonder the woke wonders have so much clout, especially when social media gives them a platform.