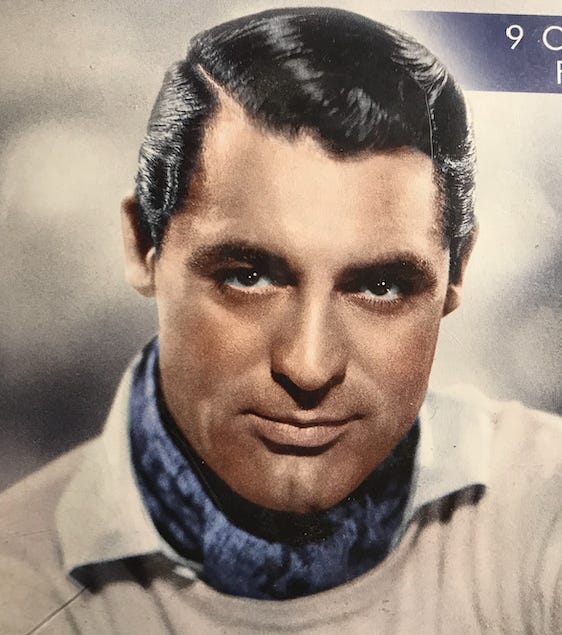

Cary Grant (1904-86) made his first short film in 1931. He hit the big time in 1932, playing opposite Marlene Dietrich (1901-92) in Blonde Venus. He made four other films that year, two of them with Sylvia Sidney (1910-99): Merrily We Go to Hell and Madame Butterfly. He would make over 70 films in his long and hugely successful career. Grant died in Davenport, Iowa, where he was touring with a theater company, ending his life on the provincial circuit, which, in some ways, resembled the vaudeville world in which he began his career in England.

Grant’s particular gift was effortless command of the screen. He was an extraordinarily attractive man who silently communicated uncertainty instead of swagger. Striking without being intimidating, he was a perfect match for the soft feminism of the so-called woman’s movie. That genre was mastered by George Cukor and Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who directed films in which the underestimated woman gets a chance to show her stuff.

Madame Butterfly shares some features of the woman’s movie. It was directed by Marion Gering, who worked with Sidney in Ladies of the Big House in 1931. He directed I Take This Woman, with Carole Lombard, also in 1931, and Sidney again in Pick-Up, in 1933. In 1932 he directed Grant, Gary Cooper, Charles Laughton, and Tallulah Bankhead in the thriller Devil in the Deep.

Madame Butterfly concerns a young Amierican naval officer, Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, who has just arrived in Japan. On the way, he has decided to marry a Japanese woman, although he has no intention of remaining in the country. The character’s mix of charm and duplicity was right for Grant’s easy ambivalence. Pinkerton never seems entirely serious. But he is serious about getting what he wants, no matter the cost to others, as men are often seen in the woman’s movie.

Pinkerton’s double-sidedness suits the narrative’s attempt to balance the harsh facts of colonialism with the painful reality of a young woman’s unrealistic expectations. Most versions focus on Cho-Cho-San, the Japanese bride, a mere teenager who must bear her family’s financial burdens.

Western fascination with Japan began in 1860, when Japan loosened its restrictive trade relations with the outside world. Jan van Rij’s splendid book, Madame Butterfly, explains how the novelty and beauty of Japonisme swept the West, influencing art, music, and design. Literature and journalism had to catch up with history. Marriage with Japanese women was a common subject in literary Japonisme. Sailors and sea merchants had long observed the custom of acquiring, for a price, a temporary Japanese wife, with the mutual understanding that the commercial contract could be broken at any time. Butterfly’s story fits squarely into this tradition.

A mix of history and fiction, what I will call the Butterfly tradition begins with a novel by Pierre Loti called Madame Chrysanthème (1887). It tells the story of a naval officer who was briefly married to a Japanese woman. This is Loti’s own story. His real name was Julien Marie Viaud; he was a French navy lieutenant. He married a woman he regarded as “a mere plaything to laugh at,” establishing a motif that runs throughout the Butterfly canon. Many French officers had a Japanese mistress or mousmé in Nagasaki. The Japanese are seen as chattering monkeys and Butterfly herself is compared to a pet cat (van Rij, p. 27, p. 33; see also Budden, p. 25). These racial elements would be modified in some subsequent accounts.

The fiction of Cho-Cho-San forms a small part of the swelling of interest in all things Japanese in the following decades, a history of America’s “romance” with Japan that is deftly summed up by van Rij. Filmmakers as well as artists and composers took up the theme. A silent movie based on a short story starred Mary Pickford; it appeared in 1915.

Navy warships, 1930

In 1932, Madame Butterfly, a movie with sound, was released. A blossom-enclosed temple seen in the film’s opening moments contrasts with the arrival of U. S. warships. The mysterious, tradition-bound, and fragile face of Japanese culture is juxtaposed to powerful gunboats sailing at the camera. Colonialism is a clash of old versus new, small versus big, shy versus bold, the flower versus the warship. The film effectively captures and juxtaposes these extremes.

The movie adheres to the main contours of the Butterfly legend, with a rash marriage followed by abandonment, but injects a refreshing, even startling inversion of the power relationship. It makes a significant and memorable contribution to the Butterfly legend, albeit one that is seldom noted. We can thank DVD collections of Grant’s many films for getting this film in the public eye.

Madame Butterfly is but one version of the story of Cho-Cho San and her unhappy marriage to the opportunistic American. In 1898 John Luther Long based a short story on Loti’s novel. In Long’s version, Cho-Cho-San speaks Pidgin English, an effect that compromises her dignity and, for me, the seriousness of the story. Long was familiar with some aspects of Japanese culture. Sources suggest that he heard a version of such a story from his sister, who had lived in Nagasaki. Long also used Loti’s novel.

A new view of the story developed when, in 1900, Long’s short story became a one-act stage version written by Long and David Belasco. The play compresses but preserves the elements in the short story. Once in Nagasaki, Pinkerton uses a marriage-broker to find “both a wife and a house in which to keep her.” He takes a lease for 999 years; the lease can be terminated “at the end of any month, by the mere neglect to pay the rent.” This is a custom; for men like Pinkerton, perhaps it is the expected thing. It was a financial transaction that was a benefit to the family of the temporary wife.

Pinkerton’s marriage seems to be a form of amusement; his young bride (just 15), is, of course, in earnest, even though she knows that her family has been paid for her marriage. At their wedding and after, in both Long’s story and the play, Pinkerton regards Cho-Cho-San’s deference to her ancestors as a puzzling encumbrance. His friend Sayre has warned him that her ancestors, who might be living or dead, “were his wife's sole link to such eternal life as she hoped for.”

In a colonial culture such as Japan was, to American eyes, roles are well-defined. It is only when someone acts against tradition that we have drama. Acting against tradition is the risk that Madame Butterfly, at her tender age, chooses to take. The creator of the first opera about the temporary wife seems to have realized that colonialism itself could not make for engaging drama.

Charles Prosper André Messager’s opera was based on Loti’s Madame Chrysanthème and was written in 1893. He is now forgotten, it seems; he was a student of Camille Saint-Saens. His opera is also forgotten, overshadowed by Giacomo Puccini’s ever-popular Madama Butterfly, which premiered in 1904. Messager made an important contribution, developing a plot centering on a test of Butterfly’s fidelity. Puccini continued the development of Butterfly’s role, pointing only briefly to colonialism and then pushing it to the background.

Versions of the Butterfly legend compete in Madama Butterfly. The librettists, Luigi Illica and Guiseppe Giacosa, favored Long’s short story. But Puccini preferred the play, which he had seen in London. Given that he did not speak English, we must ask what drew him to the work. Julian Budden has suggested that it was not the plot but rather stagecraft—and silence.

After his marriage, Pinkerton leaves Japan, promising to return. Three years later, when his ship arrives in Nagasaki, Butterfly, with Suzuki, her maid, and her child by Pinkerton, waits at a window for his return. Her behavior, however admirable, is not in keeping with the tradition of the temporary wife.

During this interval, lasting fourteen minutes in the play, the stage is transformed. Night falls, floor lights are lit, stars come out, dawn breaks, the floor lights are extinguished, and birds sing (Long and Belasco, in Narici, p. 169). Puccini loved this moment. Budden believes that a simpler scenic transformation had inspired Puccini’s music for the start of Act 3 of Tosca: dawn arrives, accompanied by a shepherd boy’s flute, as Mario awaits execution at the Castel Sant'Angelo (p. 22). In Madama Butterfly the stage picture, with slowly changing light, is accompanied by the “Humming Chorus” (it lasts about two minutes and thirty seconds).

Madame Butterfly, 1932: Butterfly, center, and Suzuki wait for Pinkerton’s ship.

This silent, still scene wonderfully conveys the Butterfly’s simple understanding of colonialism as a personal matter rather than an impersonal tradition. Successive retellings of her story leave colonialism behind. The Butterfly legend bears traces of what Arthur Groos calls a “shift in emphasis from East-West relations to character tragedy” (p. 173).

It was not an easy shift. On its way to its final reconciliation of these competing elements, for example, Puccini’s opera went through three revisions after its unsuccessful premiere in 1904; the orchestral score was finally settled in 1906. As these elements shifted from what we might regard as the public, colonial theme, to the private love story, Butterfly’s importance grew and the colonial theme, and, with it, Pinkerton’s role, shrank.

In Puccini’s opera, Butterfly is on stage the whole time, as hopeful bride, as suffering mother, and finally as abandoned lover. The opera includes a single aria for Pinkerton, a sentimental farewell to the house he shared briefly with his Japanese wife (“Addio fiorito asil,” Farewell flowery refuge). He then rushes away, saying “I am a coward.” The aria does nothing for his standing with the audience. He remains one of opera’s most scorned characters. In his immaculate uniform, Grant, of course, always looks sensational, far more dashing than most Pinkertons one sees on the opera stage.

The 1932 film Madame Butterfly (Grant and Sydney, above) incorporates elements from the short story, the play, and Puccini’s opera, which supplies some music for atmospheric effect. The movie begins with a significant moment in Butterfly’s life, a ceremony not found in Long’s or in Belasco’s version. Her grandfather and mother dedicate her in a temple and bind her to her ancestors (her father has died). Tradition comes before the individual. Butterfly can have no doubt about what this means for her. No one could be more deeply immersed in a culture than Cho-Cho-San is in hers, “even if,” as she says at the ceremony, she is “only a woman.” She will soon forget all about tradition.

The young Butterfly is brought to a geisha house by her grandfather and her mother. They are destitute and only Butterfly can earn money for the family. Willing to become a geisha, a role that did not include sexual accommodation, she is bound to tradition. But the tea house is more than tradition. It is also a place where East meets West.

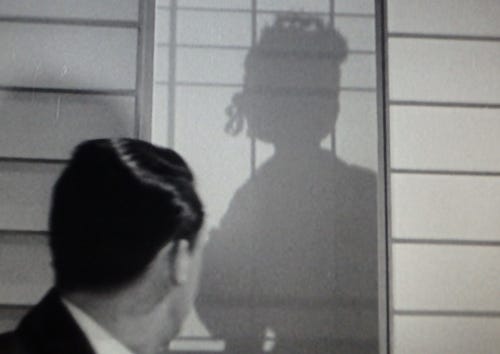

Lieutenant Pinkerton watches Butterfly dance behind a screen

We see Pinkerton and his friends visiting that house, where he sees Butterfly, who has just begun to work there. She dances behind a screen, unaware that she is being observed. Her gracefulness fascinates him. He tracks her down as she walks through the tea house, trying to elude him. He is smitten. He wants a wife and knows Japanese wives can be had for very little financial or emotional investment. For him the U.S. Navy will come first, and with it his expectation to marry the American woman of his choice.

At their wedding

Pinkerton marries Butterfly in a tradition-laden Japanese ceremony. He knows he must leave Japan soon but does not tell her. She finds this out by accident when they attend a dockside celebration. On the day of departure, at the dock, he promises to return when the robins nest, in the spring. During the time he is away—three years—Butterfly gives birth to their child. Perhaps he sees that she is no ordinary temporary wife—which establishes some culpability for him, in my view—and does not want to disappoiont her, even though he must do that very thing.

Not everyone regards Pinkerton as the villain of the Butterfly legend. He is doing what is expected of him, what many other men have done, whether in the Navy or the Merchant Marine or sea trade in other forms. He is true to his tradition; Butterfly, we know, is not. She is part of a business transaction, a tradition she understands, but she aspires to more.

In Long’s story, Pinkerton returns to Japan with Kate, his American wife. She meets Butterfly in the American counsel’s office, where Butterfly seeks information about her husband. Kate thinks that Butterfly very beautiful but calls her a “plaything,” thus echoing her husband’s view. The marriage between Butterfly and Pinkerton cannot be seen, by Kate or other colonialists, as a real marriage. Kate knows that Pinkerton has a son by Butterfly. She plans to bring the boy with her to meet Pinkerton in Kobe, where he has relocated.

Butterfly has an idea of what has happened. In Pinkerton’s room earlier, waiting on him, she discovered a photograph of Kate. I think that, at this point, her wheels begin to turn, suggesting a degree of self-awareness that we do not find in other accounts (admittedly, such revelations can be found in the woman’s movie genre).

Butterfly finds Kate’s portrait, hidden among Pinkerton’s things

In order to appreciate the boldness of the 1932 film, we need to know how the story of Butterfly is concluded in earlier versions. Long ends the tale as follows. Kate is due to come for the child. Butterfly is prepared to die with her father’s sword.

THE maid softly put the baby into the room. She pinched him, and he began to cry.

"Oh, pitiful Kwannon! Nothing?" [Kwannon is a diety of compassion.]

The sword fell dully to the floor. The stream between her breasts darkened and stopped. Her head drooped slowly forward. Her arms penitently outstretched themselves toward the shrine. She wept.

"Oh, pitiful Kwannon!" she prayed.

The baby crept cooing into her lap. The little maid came in and bound up the wound.

WHEN Mrs. Pinkerton called next day at the little house on Higashi Hill it was quite empty.

I take this to mean that Kate did not in fact find Butterfly with her son but found nobody and that she left the house, and Nagasaki, without the child.

Belasco changed the ending. In the play’s final scene, everybody concerned with the matter has gathered in Butterfly’s house except Pinkerton, who cannot face Cho-Cho-San. Kate offers money for the baby, and the American Consul is there to smooth the transaction. Kate calls Butterfly a “pretty little plaything.” But Butterfly proudly insists that she was Mrs. Pinkerton and, although now only Cho-Cho-San, is “no playthin’” (Belasco, in Narici, p. 171). This is strength, not deference.

Butterfly sends everybody away but Suzuki, her maid, then goes behind a screen with her father’s sword. Suzuki pushes the baby into the room. Butterfly emerges and clasps the baby to her breast. Kate enters and behind her Pinkerton. Butterfly has put the American flag in the baby’s hand, waves it, and then dies, saying “Too bad those robbins did n’ nes’ again.” Kate and Pinkerton take the baby.

Puccini’s ending is close to Belasco’s. Pinkerton, who is the anchor, so to speak, of the colonial element, has been absent throughout Act 2 of the opera, which focuses on Butterfly’s poverty and her unflagging faith in his husband’s return to Japan. He does not appear again until the very end, arriving with his American wife to claim the child.

Act 3 makes the most of Puccini’s instinct for pathos and shapes a memorable conclusion, showing how the prerogatives of colonialist culture crush Butterfly. She sings an anguished aria to her child: “Not for your pure eyes is Butterfly’s death,” she sings. “Go, play, play.” She blindfolds the boy, to whom she has given an American flag and a doll, and goes behind a screen to stab herself, then comes out. She stumbles toward the boy, kisses him, and dies. Pinkerton and Sharpless rush in just as she dies, Pinkerton calling her name.

Puccini’s opera is the only version many readers and viewers know. Given the towering stature of the opera (1904), we must admire the way in which the 1932 film stands the story on its head and brings us into contact with another side of the colonialist narrative.

In the film, Pinkerton and his wife come to Butterfly’s house, having had no news of her and no contact with the American consul, who plays a key intermediary role in other versions. With the help of Suzuki, Butterfly has concealed the little boy. Pinkerton and his wife do not see him. Nor does Butterfly say anything about the boy.

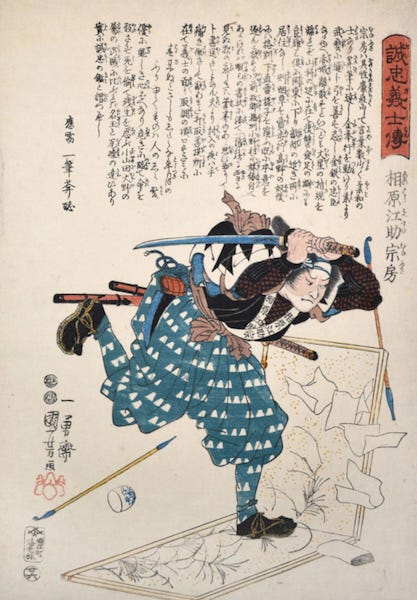

Once the Pinkertons leave, Butterfly directs Suzuki to take the boy to his grandfather so he can be raised by as a Japanese child should be raised. He will become a samurai, following the honorable tradition of his ancestors, she says. She kisses his hand, a sign of respect; earlier we have seen her kiss Pinkerton’s hand (and he hers). Now she shows respect instead for her son.

Kneeling at an altar to pray (with Pinkerton’s slippers in the foreground) she asks to be made clean. She repents dishonoring her ancestors with her marriage to Pinkerton. She asks for forgiveness if she did wrong by keeping the boy’s existence from his father. “I love you for always” she says, and then dies. Does she mean the boy, or his father?

However we read her final lines, Butterfly has proved that she is not “only a woman.” She turns out to have a compelling commitment to tradition after all. The film’s stroke of genius is that Butterfly prevents Pinkerton from learning that he has a son. She seems to have anticipated the possibility that he and his wife would want to take the boy to America. She keeps that from happening. This idea, in my view, is born when she sees the American wife’s hidden photograph and, with it, gets a glimpse of her own future.

In this single but essential matter, Madame Butterfly has triumphed. She has frustrated the colonial imperative. She has preserved Japanese tradition which, years earlier, she traded—and, she now knows, foolishly traded—for an imaginary vision of American happiness. When her illusions vanish, Butterfly discovers her steel. She makes a plan, and with it she routes the presumption built into the temporary-wife tradition. Then she chooses an honorable death, alone, unseen by her son or her embarrassed husband and his American wife.

In other versions, as van Rij notes, Butterfly is merely a victim of her own bad judgment. In the 1932 film, however, we can also see her as heroic. That is because, before she dies, she ensures that the samurai tradition will continue through her son. She determines that her son will have a Japanese future of the most honorable kind. She does not do this to spite Pinkerton but rather to atone for her previous disregard for tradition and her own heritage. Nothing could be braver than her sacrifice; nothing could be less like the cheery tradition of the woman’s movie.

Aihara Esuke Munefusa. Samurai. Woodcut print by Kuniyoshie (1794-1861). 1847.

It is important to see her strength in the context of Japan as it was in the early 1930s. We know from shots of the battleships plowing their way to Nagasaki that we are in the modern world, not in the nineteenth century, with its omnipresent Japonisme and Butterfly legend created by Loti, Long, Belasco, and Puccini.

In 1931 the Japanese invaded Manchuria. Vast military operations put Japan in control of large sections of China by 1937. Raw materials obtained through this settler colonialism, complete with bloody invasions, supported the build-up that led to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and to World War II.

Colonialism was essential to Japanese culture. It is by no means a Western vice (or, as the anti-Semites insist today, a proclivity of Zionism. The movie ends with Butterfly sending her son to be trained as a samurai—as an ethical warrior, that is, a path that was also open for girls. This is more than a nod to the steel of Japanese culture. The film silently juxtaposes an elite, individual form of discipline with the massed power of the 1932 U.S. Navy. The contrast alerts us to the realities that surrounded Madame Butterfly in the Japan of the film’s time. It also quietly points to the importance of military might to small nations as well as to great ones, a lesson that would be permanently impressed on the United States in less than a decade.

September 2024

With thanks to George Paterson.

Sources

Belasco, David. Madame Butterfly: A Tragedy of Japan. In Narici, pp. 161-72.

Budden, Julian. “Forte e nuova, ma non facile” [Strong and new, but not easy]. In Narici, pp. 22-29.

Groos, Arthur. “Lieutenant F. B. Pinkerton: Problems in the Genesis and Performance of Madama Butterfly. In The Puccini Companion, ed. William Weaver and Simonetta Puccini. New York: W. W. Norton, 1994. 169-201. (Note: Pinkerton was originally named Sir Francis Blummy Pinkerton and is referred to in the 1907 score as F. B. Pinkerton. But during the wedding ceremony he is called “Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton” and he is usually referred to as B. F. Pinkerton.)

Long, John Luther. Madame Butterfly. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/LONG/contents.html. In Narici, pp. 113-35.

Narici, Ilaria, ed. Madama Butterfly 1904-2004:Opera at an Exhibition. Milan: Ricordi, 2004.

Van Rij, Jan. Madame Butterfly: Japonisme, Puccini, and the Search for the Real Cho-Cho-San. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2001

A uniquely sensitive and moving piece here, Allen. I don't think I've seen the topic of colonialism handled this way before. I quite enjoyed it. I wonder if the tragedy of moral corruption of the coloniser is perhaps more readily available in the version with Pinkerton and Kate discovering the child and dead mother. Without the final triumph of Madame Butterfly, I wonder if the moral failure of Pinkerton might strike the heart more acutely. I don't know, since I haven't seen or read any of these stories.