Inflation has been mentioned as one consequence of COVID-19 that will not be going away. Zoom looks lilke another pandemic holdover, and so is the left’s love affair with doom. For them, the sky is always falling.

One surprising thing about the pandemic was the media’s enthusiasm for bad news about the virus and the lockdowns. The worse things were for us, the happier they were. Once the vaccine came along and COVID-19 receded, the media jumped at every chance to say bad days were coming back. “Surging” was the mantra of The Wall Street Journal: “COVID-19 surges in some southwestern Kansas communities, experts say.”

After COVID peaked, the focus was the deprivation resulting from the shutdowns that the government and its media servants demanded. The media didn’t want us to be informed; it wanted us to be alarmed. The tighter the government’s control became, the more influence the media enjoyed. If you doubt that the media serve as a megaphone for Democratic politicians, read Matthew Hennessey’s essay, “The Democrats’ Trump Concussion.” He writes that today, in the early phase of Trump 2.0, Democrats are “dazed, moaning and babbling.”

Christopher F. Rufo has traced the history of Trump hysteria, which began eight years go. On Feb. 17, 2017, The Washington Post unveiled “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” which Rufo describes as “their big Resistance hashtag, and their anti-Trump rebranding.” On cue, 17 agencies signed off on claims that Russia had controlled the 2016 election (“Trump’s Extraordinary Opening Moves”).

After that, the media existed to serve the Democrats; their story would be the only one that would be told. This is still true, whether you read The Wall Street Journal, once a sensible news source, or The New York Times, which has not been sensible for decades.

The media live for bad news. Doomsday scenarios, negative emotions, and exaggerations are catnip to woke commentators. On Election Night, CNN host Van Jones lamented that Black women and Hispanics had started the day “with a dream” and “were going to bed with a nightmare.” The sky is falling!

A colleague asked him why he was sure that these same people had not voted for Trump—as, it turned out, significant numbers of them had. Easy to answer. When talking about his audience, Jones was really talking to himself about his personal dream and his own nightmare. He was both the star and the audience in his private theater of emotion.

The stellar Christine Rosen has tracked some woke responses to the election, which is the most recent event to evoke woke catastrophizing.

The editor of New York magazine wrote to subscribers that he felt “disappointment, fear, anger, and alienation” (Rosen, p. 10). He was sure his readers felt the same way. What were he alienated from, if not America as it exists outside coveted Manhattan ZIP codes and other elite circles? He thought we were his friends!

Also lost in gloom was Lisa Lerer of The New York Times. Ignoring the restraint we used to expect of journalists, she predicted a grim, totalitarian Trump era. Under the headline “American Hires a Strongman,” she wrote, “This is a conquering of the nation” (Rosen, p. 10).

I wonder if Lerer knows what “conquering” means. It means to overcome by military force; to overcome a weakness; or to take possession of something. Trump did not take possession of the U.S. by winning the election. Nor did he overcome a weak nation, or become a military conqueror. Trump beat Harris, but, in the popular vote, just barely: 77,303,573 votes to 75,019,257, a margin of about 1.5%. Close to half the voters did not support him. A margin of victory so small is hardly a conquest or a conquering. If Trump overstated his victory, so did Lerer: opposite sides, mirror images.

Lerer claims that “America stands on the precipice of an authoritarian style of governance never before seen in its 248-year history.” A style of authoritarianism “never before seen”? She forgets the government-imposed COVID-19 shutdowns of 2020-21. With such a short memory, Lerer has no business generalizing about two and a half centuries of American history. She does not connect her feelings about Trump’s alleged authoritarianism to the feelings of those who found the shutdowns authoritarian. Nonetheless, they are mirror images. Her prediction of “an authoritarian style of governance” with Trump is amusing. It was the great Barak Obama who boasted that he needed only a pen and a phone to bypass Congressional approval. Beat that for “an authoritarian style.”

The Democratic-media machine has fantasized about Trump’s tyranny, although it was silent about Biden’s authoritarianism. Progressives still deny “that the Biden administration and other government officials had tried to force private social media platforms to manipulate and even censor Americans’ speech” (Hunter). They pretend that Biden did not try to create a “Disinformation Governance Board” within the Department of Homeland Security so he could have his own Ministry of Truth. Big Brother is always right, as far as the left is concerned.

Woke commentators use exaggerations and stereotypes (dream, nightmare, strongman, conquering) to express their feeling—emotional assertions, not analysis. Their overstatements express a “Chicken Little” state of mind. Obsessed with catastrophe, the commentators prefer inference to evidence. They decry extremism on the right but exhibit extremism themselves. They offer us yet another example of René Girard’s “mimetic rivalry,” a process in which sworn enemies start to resemble each other. After all, the New York editor’s “disappointment, fear, anger, and alienation” neatly sum up the feelings of many Trump supporters prior to the election.

Showing the strain of an election their side lost, commentators like Lerer and Jones let it all hang out. (For examples of similar overexcitement, see Feldstein and Dray in sources, below.) The path to their confessional candor was smoothed by a new category known as Explanatory Journalism (EJ), which really ought to be called Emotional Journalism.

At one time, journalism was said to have four registers: news; investigative reporting; opinion, often in its own section—reviews, editorials, and letters to editors; and features, chiefly “background” pursued as interviews and human interest stories. News and investigative reporting by definition kept the writer out of the mix. This is no longer true.

Reporting has been evolving, and the pace has been accelerated by social media. The supposed gold standard of reporting, the Pulitzer Prize competition at Columbia University, offers a useful guide.

“Reporting,” the original Pulitzer category from 1917-1947, was split into three divisions in 1948: national, international, and local reporting. Today the Pulitzer website lists seven categories, including audio, breaking news, explanatory, illustrated, international, investigative, and national.

In the area of explanatory reporting, which was added in 1997, the winner described as “a distinguished example . . . that illuminates a significant and complex subject, demonstrating mastery of the subject, lucid writing and clear presentation, using any available journalistic tool” (Pulitzer Prize). Note “the most disinterested” on the prize medallion above. We will see that “mastery of the subject” usually means treating only one side favorably and drawing conclusions that the judges have already reached.

The Pulitzer Prizes favor didacticism and emotional representation, not disinterest. Emotion is prominent in descriptions of recent awards, which emphasize woke concerns (emphasis added). They do not sound “disinterested” to me.

2023 The Atlantic. “For deeply reported and compelling accounting of the Trump administration policy that forcefully separated migrant children from their parents, resulting in abuses that have persisted under the current administration.

2020 The Washington Post. “For a groundbreaking series that showed with scientific clarity the dire effects of extreme temperatures on the planet.”

2019 The New York Times. “For an exhaustive 18-month investigation of President Donald Trump’s finances that debunked his claims of self-made wealth and revealed a business empire riddled with tax dodges.

The Pulitzers reward journalism that espouses woke beliefs. There are no investigations of protected leaders like Biden and Harris. Mainstream media shunned inquiry into the Biden family’s wealth and hid his mental decline. Also ignored was Hilary Clinton’s funding of the Steele Dossier, a collection of fabricated charges about Trump’s collusion with Russia—with the FBI’s cooperation. There are no prizes for “searing” and “exhaustive” explorations of these topics.

Instead, in 2018 Pulitzer Prizes went to The New York Times and The Washington Post for “for National Reporting on Russian interference to help Trump win the 2016 election.” Both papers were sucked in by a Clinton-funded hoax, but we should not expect their prizes to be sent back (Shelley). The writers and their readers were easily duped. Clinton sat in the background, smiling. She knows that dogs eat their own vomit.

EJ seems to have been designed to help social media package the news. Jonathan Vankin writes that the aim of EJ is to “provide essential context to the hourly flood of news.” EJ looks to “the nuance behind the facts” in order to mobilize “a rich array of relevant information made possible by new technology” so that it can be “presented to the public in accessible and digestible formats.” EJ is focused on stories that affect “daily life in ways that most of us rarely think about.”

EJ resembles “the hook” of the traditional feature story, a point used to catch the reader’s attention. EJ is not about catching attention but rather advancing a cause. EJ is not confined to the Pulitzer elite. It pops up in newspapers every day. You could hardly find better examples than articles by Rachel Wolfe and Matt Barnum in the The Wall Street Journal.

Stories about men and boys “falling behind” are a regular feature of WSJ. In September 2024, Wolfe, an economics reporter, published “Gender Gap Widens: Young Men in U.S. Keep Falling Behind.” In January 2025 WSJ published an article by Barnum, an education reporter, “Long the Star Pupils, Girls are Losing Ground to Boys.” The EJ in these essays is emotional, not explanatory. Falling behind, losing ground: versions of the falling sky.

Wolfe’s “Gender Gap” essay offers a digest of feminist stereotypes about men. Men in their 20s and early 30s are much more likely than female peers to live with their parents, and many say they feel aimless and isolated. We’ve heard it al before. Men can’t share their feelings; they prefer to be by themselves; they only care about work; or they don’t want to work.

The words “why” and “cause” appear nowhere in Wolfe’s essay. Nor do the experts she quotes mention causation. Her work is merely descriptive. It explains nothing (Latin explanare means “to make intelligible,” literally “to flatten out”). It demonstrates no curiosity about the phenomenon it documents or about possible remedies. Yet readers must wonder why young men are behaving as they do. Wolfe never mentions schools, education, or feminism. Does she offer no explanation because she needs to protect feminist and progressive institutions from accusations of bias against men? Is that why she has no sense of the history of this problem?

We might expect that, if young men are “falling behind” today, they did not used to be behind. Or were their fathers and grandfathers also “behind”? If not, there must be a reason for this change, and it is not far to seek. Young men have been raised in a culture that ridicules masculinity, demonizes men, and associates maleness with, not to forget the canonical feminist ideal, toxicity.

Masculinity is toxic to progressive feminists, who are not about to give men credit for what they do or have done. Men are discouraged by institutional misandry, the hatred of men that is rampant in the slowly collapsing DEI universe. Many astute commentators have pointed this out, including Bettina Arndt, Jack Donovan, Janice Fiamengo, and Tom Golden, justly celebrated writers and thinkers. Yet one continues to find essays like those by Wolfe and Barnum that pay no attention to work about the causes of social prejudice against men.

Women, Barnum notes in his essay on girls, have made “longstanding gains” in education, meaning that for a long time women have been ahead of men in education. (I am troubled by his word choice. Longstanding means “in existence for a long time.” How is a “gain” in existence for a long time?) For his purposes, it is better to refer to women making “gains” (they are still going uphill, that is) rather than “outperforming” men, even though, in all educational areas, women outperform men.

At the start of the pandemic, girls were in the lead all around, even math and science. Since 2019, however, girls’ math and science scores have dropped at a “more severe” rate than boys’ scores, as Barnum puts it, again oddly. Why is a rate “severe” rather than “sharp” or “marked”? I conclude that a rate is “severe” when you need to present the affected group (girls) as endangered.

In his essay, explanation is replaced with assertion. An education expert from the University of Rochester notes that girls “have a comparative advantage in school” (a version of “longstanding gains”) and claims that, without school, “they’ll suffer more”—more than boys, I assume.

Since boys lack “a comparative advantage” in school, won’t they suffer more without school? If boys can’t do well with teachers’ assistance, how well will they do without it? The logical expectation is that girls who do better in school would do better outside of school also if they chose to.

Not surprisingly, Barnum and his sources attribute the girls’ loss of learning to boys. He notes that there were behavior problems “during the pandemic years.” As a result, teachers began to “pay more attention to boys, who tend to act out more during class.”

NPU: “Our kids, our voice”? Sounds like child abuse to me.

Barnum quotes the New York state director of the National Parents Union (NPU), who says that her daughter “spent much of the year at home watching videos” while her mother worked—at home! Mom, state director of the National Parents Union, let the television and the iPhone babysit her child while she herself worked on union business. No comment from Barnum. The daughter was poorly prepared, thanks to her mother. But then, her daughter does not pay union dues.

Another mother points out girls are penalized for behaving well. Her daughter is well-behaved and so is “easy to overlook” in school, whereas trouble-causers (guess who they are?) get attention. Does this mom think that the attention that the troublemakers get is helpful to their education? If the extra attention troublemakers get is educational, why aren’t the troublemaking boys doing better than compliant girls? Where is that “comparative advantage” we just read about?

If boys are not doing well, it is the boys’ fault. If girls are not doing well, it is also the boys’ fault. Barnum believes this. Explanatory journalism helps him embed anti-male prejudice in his essay. He quotes mothers rather than fathers. Does he think that only mothers are experts on daughters, and that mothers have no feelings about their sons? Boys act out, but their behavior is assessed only in terms of its effect on girls’ learning. The boys’ own learning gets no attention whatsoever. Equally significant is Barnum’s failure to consider the impact of social media on learning by girls or boys or to comment on differences in maturity rates between girls and boys.

We see more emotional identification in an essay by Wolfe about both women and men. This essay too is strangely silent on causes. In “What Happens When a Whole Generation Never Grows Up?”, Wolfe quotes 30-somethings who don’t know how to grow up and have not had to. “It feels like the instructions for how to live a good life don’t apply any more,” one man says, “and nobody has updated them.” Dear me! A toy in a box, but no instructions for assembly.

You would never guess it, but this man is co-owner of a business, according to Wolfe. Sympathetic expert commentators argue that young people like him “can’t afford to grow up.” But why can’t they? Wages after the pandemic leapt up. Many people in the 20-40 age range sat out this growth, moving in with families that were, it seems, eager to welcome them back to the nest.

The claim that young people “can’t afford to grow up” is easily disproved by Wolfe’s own data. “Median wages for full-time workers ages 35 to 44 are up 16% between 2000 and 2024, from $58,522 to $67,652 adjusted for inflation” (Labor Department data). In addition, the wealth of 30-somethings “rose 66% between 1989 and 2022, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, from $62,000 to $103,000.”

Wolfe writes that “this age group is in a better place financially, on average, than their parents were at this age. The problem is that they don’t seem to know it.” They are more pessimistic about the future than their parents and grandparents were. They think a starting salary of $70,000 is too low to bother with. It seems that “many 30-somethings sound disoriented and unsure about what it means to be a successful adult now” (“What Happens”).

How can anybody at 30 be unsure of what it means to be a successful adult? It means, first of all, to be able to support yourself; to have personal and professional goals; and to have knowledge that makes you useful to society. Have these social dropouts heard of Google? If you Google “how to be a successful adult” hundreds of sites come up, many of them offering sensible and specific advice. How can this connected generation have failed to show enough initiative to type a few words into a search engine?

They don’t know that wages in their age group have risen markedly. They also don’t seem to know—and here is the rub—that they have to work for what they want.

Rufo has written about young people like those Wolfe discusses. Rufo’s essay is titled “Is Gen-Z Doomed? What it takes to make it in America.” He’s not only talking about “making it” in terms of salary. If young people are “doomed,” they are dooming themselves by living in a social media bubble that prevents them from dealing with economic realities. If they are doomed, it is because, as a result of their passivity, they have no grit, no fight. They have allowed social media to beat them into submission. They believe that the sky is always falling: the Chicken Little genderation.

The young have unrealistic expectations about where they can live and believe that they must live where they want to live. They exclude flyover territory—St. Louis is mentioned in Rufo’s article—and favor Manhattan, Malibu, and other expensive areas. Economic conditions are seldom just right. Some things are out of reach. “As an individual, you have to adapt to them,” Rufo writes, “and you have to fight and struggle to put your own life together the best way that you can.”

In other words, you have to sacrifice. Nobody needed to tell my generation that.

In truth, it does not matter how Gen-Z obtains what little information it has, since most media are committed to progressive views and seldom focus on positive news. If young adults are indeed “significantly more pessimistic about the future than prior generations were,” as Wolfe and others claim, that is partly because progressive news sources want them to feel that way. We all know that bad news is, for the media, good news. Unemployment, hiring freezes, and strikes make the news. Successes fall into the secondary category of “human interest.”

So pronounced is the tendency to focus on the negative that, long before Trump’s second inauguration, it had an name: doomscrolling, defined by Makal Alibert as “the compulsive activity of pursuing negative news online.” Not surprisingly, this compulsion is unhealthy in every sense, disturbing sleep, and destroying peace of mind. Alibert notes that news headlined with negative words draws more eyes and is more likely to be shared on social media.

There are lots of reasons why bad news pays off. For one, people really do need to be aware of dangers around them, whether falling on black ice or being taken in by an insurance scam. Knowing the news also gives a feeling of control: I know what’s going on around me. But this awareness also creates stress and reinforces a sense of powerlessness. Checking stories on your phone creates the illusion of control, which is all some people need.

The experts, like the journalists, focus on problems that have no solution. Economists such as Carol Graham of the Bookings Institute blame the disaffection of young people on climate change, political polarization, AI, and, ominously, resentment of corporate power (Wolfe, “What Happens”). These conditions are excuses used to explain why men and women in their 30s are sleeping in the rooms in which they grew up. Young women and men are persuaded that they are victims of forces beyond their control. They feel that the future is uncertain.

But, in life, the future is never certain.

Gen-Z has failed to learn a lesson, and their elders have failed to teach it to them. What matters in achieving success is how much you are willing to give in order to get what you want. The people Lerer and Rufo write about are their own worst enemies. They don’t know what they want, so of course they have no idea about how to get it. They are aided by doom prophets, the sympathetic commentators whom the doomscrollers scroll.

Wolfe does not mention social media, the chief cause of the trend she highlights. The reason is not far to seek. Unlike AI, climate change, and similar phenomena, there is no excuse for social media addiction except addiction—a lack of self-control. A phone can always be put down. But a phone offers the comfort of powerless spectatorship. Do less, scroll more.

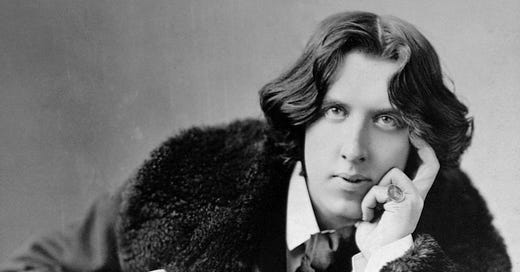

In Oscar Wilde’s “The Critic as Artist,” the character known as Gilbert says that “there is much to be said in favor of modern journalism,” since, “by giving us the opinions of the uneducated, it keeps us in touch with the ignorance of the community” (1891; p. 987).

There is much to be said in favor of EJ. It keeps us in touch with modern journalists’ tendency to confuse opinion with knowledge and to excuse the ignorance of the community. Balanced perspective, which requires reason, moderation, and, above all, a grasp of cause and effect, is passé. Wilde wrote about “the decay of lying.” What we see today is the decay of its opposite.

January 2025

Sources

Alibert, Makal. “How Doomscrolling Steals Our Health.” The Epoch Times. Jan. 22-28, 2025. B10.

Barnum, Matt. “Long the Star Pupils, Girls Are Losing Ground to Boys.” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 6, 2025. A3.

Dray, Kayleigh. “Trump's victory reveals just how mainstream misogyny has become: It’s a stark reminder that we are never far removed from the dystopian nightmare of The Handmaid’s Tale.” Cosmopolitan. Nov. 6, 2024. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/reports/a62828180/donald-trump-election-feminist-response/

Feldstein, Steven. “Will Trump Govern as a Strongman”? Emissary. The Carnegie Endowment. Nov. 7, 2024. https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2024/11/trump-authoritarian-strongman-govern-signs?lang=en

Hennessey, Matthew. “The Democrats’ Trump Concussion.” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 30, 2025. A15.

Hunter, Jack. “Where Is Democrats’ Outrage at Biden’s Authoritarianism?” June 10, 2024. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/where-is-democrats-outrage-at-bidens-authoritarianism/

Lerer, Lisa. “Trump Asked for Power. Voters Said Yes.” The New York Times, Nov. 8, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/06/us/politics/trump-election-analysis.html

Pulitzer. The Pulitzer Prizes. Columbia University. https://www.pulitzer.org/prize-winners-by-category/207

Rosen, Christine. “The Suicide of the Mainstream Media.” Commentary. December 2024. 8-10.

Rufo, Christopher F. “Is Gen-Z Doomed? What it takes to make it in America.” January 17, 2025. https://christopherrufo.com/p/is-gen-z-doomed?utm_campaign=email-post&r=14kc55&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

——- “Trump’s Extraordinary Opening Moves.” January 31, 2025. https://christopherrufo.com/p/trumps-extraordinary-opening-moves?utm_source=podcast-email%2Csubstack&publication_id=1248321&post_id=156144458&utm_campaign=email-play-on-substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=play_card_post_title&r=14kc55&triedRedirect=true

Shelley, Susan. Pulitzers for the ‘Russiagate’ hoax should be returned.” Los Angeles Daily News. June 8, 2024.

https://www.dailynews.com/2024/06/08/susan-shelley-pulitzers-for-the-russiagate-hoax-should-be-returned/

Vankin, Jonathan. “Explainers, Explained: Explanatory Journalism, and Why California Local Does So Much of It.” California Local, Oct. 22, 2021. Seen Jan. 10, 2025. https://californialocal.com/localnews/statewide/ca/article/show/810-explanatory-journalism-explainers-explained/

Wilde, Oscar. “The Critic as Artist.” Intentions, 1891. In The Works of Oscar Wilde. Enderby, Leicester: Blitz Editions, 1990. 948-98.

Wolfe, Rachel, “Gender Gap Widens: Young Men in U.S. Keep Falling Behind.” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 9, 2024. A1, A6.

-——. “What Happens When a Whole Generation Never Grows Up?” The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 31, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/economy/what-happens-when-a-whole-generation-never-grows-up- d200e9ef.

I've been noticing that addiction is a major issue for Gen Z, not just social media, but all manner. So even if they are employed and earning well, it's often in the meaningless and soul-destroying sector of financial products. Life becomes a dissociative affair often expressed by the motto, "Work hard, party hard."

Excellent article Allen. I really enjoyed reading this one and particularly loved the Chicken Little reference. Totally true and hilarious! Thanks too for the mention. It is fascinating to watch the TDS sufferers and I must admit a part of me finds it satisfying in some way....seeing the crash and burn of such misguided hatred has its moments.