Buttoned Up:

Hooks and Hookers in Victorian London

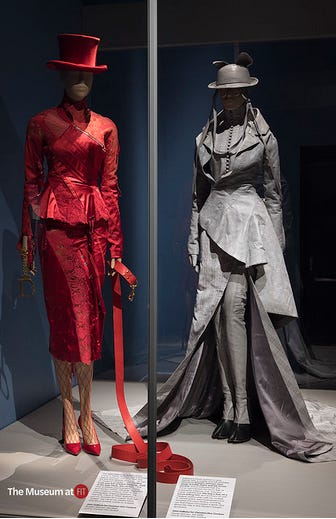

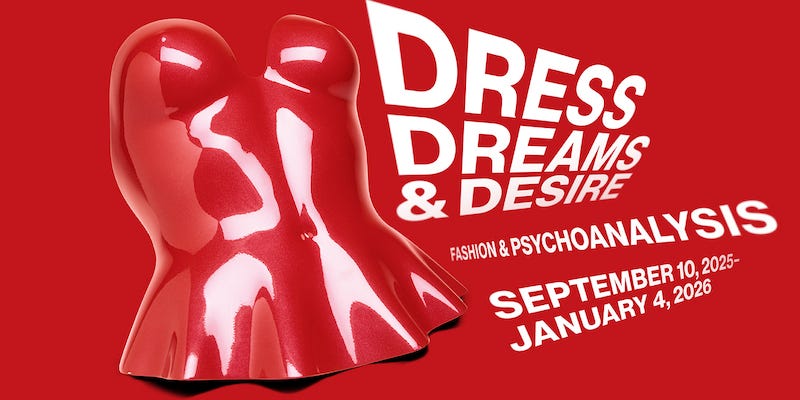

Exhibits about the future of fashion seem to recoup fashion’s past. The new look needs the old one in order to be seen as new. “Dress, Dreams, and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis,” now at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT, a splendid acronym) encompasses the most daring new designs but also nods to high-button shoes, breath-taking corsets, and other Victorian conventions. Message received: confinement then, freedom now.

Fashion is never just about clothes. FIT’s exhibition tries to get inside them by raising the specter of Freud and poststructuralist thinkers, ranging from Jacques Lacan (1901-81) to Judith Butler (b. 1956). FIT suggests that there is something sinister about fashion, old or new.

The Victorian age gave birth to psychoanalysis, which attempts to decode human behavior by finding the “why” behind every “what.” In this case, “what” comprises buttons and button hooks. Why were these devices central to women’s fashions?

The Age of Victoria made buttons indispensable. The dresses of every fashionable woman included many buttons, and her purse contained a buttonhook and maybe more than one. Even doctors carried buttonhooks, in case they have to help a patient out of her dress, or her boots.

There’s an example of a doctor so equipped in Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White (2002), which offers an encyclopedic view of the Victorian age. Dr. Curlew arrives at the home of industrialist William Rackam to attend Sugar, the governess he employs, who has taken a fall. William had been one of her customers in her recent career at Mrs. Castaways’ aptly-named house of prostitution. He is married to Agnes, a sad, mad Victorian woman. Arriving at William’s home, Curlew “removes [from his bag] a sharp metallic instrument, which proves to be a buttonhook” (p. 750). Faber offers a small joke at Curlew’s expense. The curlew is a bird sometimes described as having “a long, curved bill, evoking a hook,” perhaps like the one Curlew carries (Wiki).

Above, a Victorian button hook; below, a hook today

Readers already know, and the doctor soon discovers, that Sugar is pregnant. We might wonder if he will use his hook to perform an abortion. He does not, but later he informs William of the governess’s condition. Hearing that Sugar is pregnant (with his child, we presume), William dismisses her (pp. 786-87). He is no model of courage. When Dr. Curlew prepares to come to the house with strongmen to take Agnes into confinement, William flees to Somerset to avoid the unpleasantness and to drink away his guilt.

Sugar has moved up in the world, but some of her old friends, Caroline among them, continue to work in Mrs. Castaway’s establishment. When Caroline returns to her room after walking the streets, she sometimes sleeps with her boots on because she can’t “face the thought of unhooking those long rows of buttons” (p. 8). Even prostitutes need their rest, and Caroline knows that a maid—but not a lady’s maid—will change the sheets tomorrow. It would take a while to get out of these:

Caroline’s boots call attention to her mostly hidden but alluring legs. In the Victorian period, with its sweeping skirts and trains, views of women’s legs had power. William’s pious brother Henry, no connoisseur of the ladies, sees a woman carefully crossing the street. She looks respectable, but “when she sees Henry, she lifts the hems of her skirts higher than he’s ever seen hems lifted—revealing not just the toes, but the whole buttoned shank of her boots, and a glimpse of frilly calf as well.” As she does so, she smiles at him (p. 319). This woman is not respectable after all. We can’t be sure, however, that Henry reaches the same conclusion.

The novel neatly frames the contrast between Agnes, an oppressed, very wealthy Victorian wife, and Sugar, one of the 200,000 prostitutes, who, like Caroline, were said to inhabit London at the end of the nineteenth century (a figure reported by the book’s narrator, who, as a tool of Faber’s playfulness, also disputes it, p. 39).

Any woman who dressed for show had to have a button hook close to hand (or to have a maid with one). Sugar makes do with the alternative. Dressing for a meeting with William, Sugar “wields a pair of ‘whore’s hooks’—curved, long-handled instruments so nicknamed because they enable a woman to don a lady’s dress without the aid of a maidservant” (p. 342).

William, Agnes’s drunken and philandering husband, is Sugar’s regular client. It is no surprise that Agnes is lonely and that she searches for spiritual guidance and companionship. Her inward journeys expand a life that offers her little freedom, in her home or out of it.

Agnes flirts with Roman Catholicism and secretly attends Mass; Roman Catholicism is not a done thing among the English well-to-do. In church, “opening her new purse under the light of the altar’s candelabra, she removes, from amongst the face-powder shells, smelling salts and buttonhooks, a much creased and tarnished Prayer card, on one side of which is printed an engraving of Jesus” (on the other is an indulgence prayer, p. 386). A “face powder shell” today:

Agnes carries several button hooks. Along with smelling salts, they seem to give her a sense of security. She feels vulnerable and abandoned, even though she is confined—and protected, after a fashion—in every aspect of her behavior. But the button hooks give us some small hope that Agnes can, if she has to, do something for herself. We will see that she has some grit.

Sugar too is boxed in, subservient to her clients’ whims and cut off from her own history (her given and last names are not mentioned). But she is also something of a tyrant, skilled at manipulation, sexual and otherwise, to get her way. Not only glamorous, Sugar is also educated, thanks to schooling she had before her mother, now Mrs. Castaway, forced her into prostitution. Sugar can match William’s literary knowledge quote for quote and has read new books that he has not. Other prostitutes are amazed at how much she has read. Sugar is also writing a book, and her comrades wonder if she will put them in it. We never find out. We do know, from excerpts Faber supplies, that Sugar fantasizes about bringing men to violent ends. She is popular because she can talk to men as well as satisfy them sexually. For then, she is work and play, or at least mind and body, in one.

Agnes stands for a fading phase of history, whereas Sugar points to the age to come. Agnes can’t seem to think outside conventions; Sugar is unable to live within them. Faber reminds us often that Sugar sees herself as a modern woman. Determined to drag William into the future, she tells him that he too must be modern (ch. 17, ch. 24).

Sugar has a head for business, and that is the foundation of her modernity. She patiently listens to William’s complaints about the supposedly unsolvable problems of his father’s large and profitable soap business. She frequently suggests how these difficulties can be managed and even turned to his advantage. Gently mocking his company’s antiquated advertising copy, Sugar rewrites brochures, revises label designs, and in other ways shows us that, when it comes to selling things to women, William is clueless. He merely repeats what his father did, whereas Sugar knows what to do. His business is based on women; he knows nothing about them.

William see that Sugar is more business-wise than he is, and more competitive. Near the end of their time together, when things between them have soured, a resentful and sodden William rages to himself about “her masculine appetite for business.” He thought she was “an erotic parlour frolic” but she was really “a monster” instead (p. 817). Masculinity is monstrous in her case because it describes the actions of a woman who knows more than a man.

Sugar’s superior business sense is a habit she developed as a woman who had to earn her living the hard way. Her tutor, and her first madam, is Mrs. Castaway, who introduced Sugar to prostitution when Sugar was thirteen. It’s not surprising that, six years into the profession, Sugar is astute. Seeing that William is smitten with her, she finds out his address. As Sugar stands outside the Rackhams’ house, Agnes looks out her window and sees a beautiful, well-dressed stranger. Agnes waves, and Sugar returns the gesture. Agnes decides that the visitor is a guardian angel who has been sent in answer to her prayers (pp. 287-88).

Agnes tells William about her vision at lunch. William does not know that Sugar has seen his home, and he takes Agnes’s comments on her guardian angel as another sign of her madness. He tries to change the subject. In an impressive show of strength, however, Agnes faces him down. There is more to her than we had thought. She angrily tells William that he believes in nothing, using “a low, ugly voice he’s never heard from her before.” She calls him a “fool” and adds, “You make me sick” (p. 290). Shocked, he leaps to his feet and upsets the table, knocking burning candles to the rug-covered floor. He has to douse the fire with his bare hands.

William later tells Sugar about the angel Agnes believes she has seen. Feeling guilty, Sugar says nothing about her part in the little drama that took place between Agnes and her; she tells herself that waving back to Agnes was the only thing she could have done (p. 295). Later, when Agnes dies, Sugar will move into the house as the governess of Sophie, the daughter of William and Agnes.

It seems incredible that Agnes should have a daughter, for Agnes knows nothing of sex or of childbirth, even after she has had a child. That is an experience Agnes cannot comprehend and that nobody has explained to her as either girl or woman. As a result of her extraordinary ignorance, she has never seen her own daughter who, in turn, has never seen her. William is complicit in this psychosis, as is Dr. Curlew, paired icons of exploitation.

Sugar rises in the world, but her options are limited. William enlarges them. We have had a thorough view of her past. Faber excels in details. He describes how prostitutes cleansed themselves between their customers’ visits and, of course, how other women tried to protect themselves. The bowl Sugar uses for this sponge-and-water sanitary ritual is emptied for her by a boy, perhaps ten, who does menial tasks for the women in the house. Innocence and experience? Not quite. How innocent can he be, waiting on prostitutes all day and half the night, and handling an object filled with murky leavings that speak of women’s bodily functions and attest to their servility, as well as to is own? When William sets Sugar up in a modern apartment of her own, she almost forgets that it comes complete with a bathroom, running water, and a toilet like this “Victorian” model you could buy today.

Faber shows us that ordinary people are skilled at reading the status signs of the rich. When she arrives in London, Sugar takes a cab to Mrs. Castaway’s address. When the near the house, she tells the driver to stop short of the actual address. “This will do!” she says, and tells him that she feels “giddy” and needs a bit of a walk. She wants to keep her distance from the driver and not to seem too familiar, or “rogue to rogue.” But she has already said too much. “Her candor with him [the cab man] counts against her; she cannot be what he at first took her to be.” He tells her to “watch yer step, miss,” with a knowing grin (p. 278).

Later, when she has lived in William’s house and realizes that she had more freedom at Mrs. Castaway’s, Sugar decides to run away and to take Sophie with her. But she has to bargain with the coachman. He knows she is up to something and demands that she submit to sex with him before she and the child can leave. The cab man, like maids and man-servants, is a useful barometer of the status of workers. They seem to be able to leverage their subordinate status as the cab driver does here. The rich are not as free as they seem.

The button hook was an essential device for well-dressed women. Like the buttons, the hooks point to restraint and confinement. Women outside society—prostitutes like Sugar—had access to devices that enable their independence. They can do and undo their own buttons. If such women were too tired at the end of the day to unbutton their boots, they could, like Caroline, wear them to bed.

Married women seem to be versions of Agnes, icons of fashion confined by their social standing. Sugar might envy married women their financial security. But like the cab man who looks down on her, she looks down on married women. Her power comes from her independence, whereas whatever power well-placed women have comes from the men they have married.

The dreams and desires of people in Victorian London emerge vividly in Faber’s book. If the novel’s 833 pages put you off, then watch the four-part television serial of the same name directed by Marc Munden, with a screenplay by Lucinda Coxon (2011). The cinematic version is superior in several respects, but not all.

Not surprisingly, the film makes nothing of buttons, buttonhooks, or other small objects that reveal status in historical periods. These and countless other details fly by on screen. Having time to think about them—and their modern forms—is one of the rewards of reading. The camera processes a lot, but we lose a lot in the process.

October 2025

Hello there Allen, you post some great content, I just wanted to comment and introduce myself.

I’ve been here a month, and I write about history, drawn from old books, and discussed in a philosophic way.

I collect historic books you see, I have 22 in my collection up to now (1707-1822).

This article discusses some of the most interesting claims from the 18th century, I thought you’d enjoy it.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/a-look-into-the-18th-century?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios