Boxing sometimes pops up outside the boxing world. You see a ring scene in a Netflix episode or read a novel in which somebody remembers boxing in the Army. It’s brief, but the reference does some work. The same is true when boxing pops up in life.

Boxing says something. References to other sports, tennis or softball or golf, say, are less pointed. Those sports—not to put them down—seem to be part of the cultural wallpaper, blandly suggesting community-building, or status or social connection, or, less often, competition disguised as leisure.

Boxing is for a rough crowd. A dark, spotlighted, indoor sport, sweaty and often bloody, boxing sharpens the focus on whatever tension is in the air. Trouble is an opportunity for discovery. Trouble is the heart of drama and the heart of boxing. I look at two contexts for boxing: a classical music conductor who boxes, and lawyers at war in “Black and Blue,” an episode of Better Call Saul.

Howard and Jimmy square off

In “Black and Blue,” part of season six, boxing is interposed into a long-running battle between Howard Hamlin and Jimmy McGill. Hamlin is a high flyer at HHM, a prestigious firm formerly known as Hamlin and McGill, named after Howard’s father George and Jimmy’s brother Chuck. Jimmy McGill is a bottom-feeder, a duplicitous ambulance chaser, grifter, and thief. Howard is CEO at HHM, which stands for Hamlin, Hamlin, and McGill—Chuck McGill, however, not Jimmy, who is overshadowed by both Howard and Chuck.

Standing between Howard and Jimmy is Kim Wexler. Even when she was just an intern at HHM, she was highly regarded. She leaves HHM to become head of the banking division of another law firm. Then she takes up pro bono volunteer work. But her descent is not quite complete. She and Jimmy form twin law firms. Hers, for a time at least, is respectable. Eventually she becomes Jimmy’s criminal sidekick. Apparently in love, they marry. They become equals, her loss, his gain.

Jimmy and Kim embark on an elaborate scheme to destroy Howard’s career, pretty much for their own amusement. Kim resents Howard, who was her boss at HHM. Jimmy resents any lawyer who can afford the trappings of power that have eluded him—nice office, nice car, nice clothes, nice trials. Kim’s motivation is far less clear. Her slide from a ponytailed new hire in trim pantsuits and heels to a blowsy go-along get-along sidekick is one of the program’s signature perverse strokes.

Kim, dukes up

Kim falls Jimmy, an inflated balloon of a masculine man. She is an amoral, self-centered hedonist. Her own satisfaction is her highest good. Eventually, at parting, she tells Jimmy that he has given her the time of her life. Considering the corruption and destruction with which they have amused themselves, her comment marks her as emotionally and ethically impoverished, smarter but not better than her husband. Near the end of the program, I know, some viewers see her fortunes rising.

One day Jimmy is contacted by a Mr. H. O. Ward, who poses as a potential client and asks Jimmy to meet him at a boxing gym. H. O. Ward turns out to be Howard. He wants to settle his personal and professional differences with Jimmy in the ring. It doesn’t work out that way.

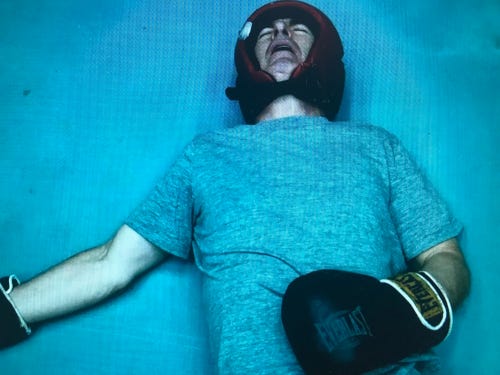

It’s a formal event. A referee gives instructions to the boxers. Jimmy clowns around, his footwork a parody of good boxing. Howard, however, is serious. He whiffs a wide swing with his left but lands a deft shot with his right. Jimmy gets in a right hook to the body and laughs. Howard’s counterpunch knocks Jimmy down, but Jimmy comes back with a pair of hooks. Then Howard lands a shot to Jimmy’s chin.

Jimmy agonistes

When Jimmy knocks Howard down at 1:49, the men seem evenly matched. But when Howard lands a direct shot to Jimmy’s gut and another to his head, Jimmy is down. Jimmy stays down. “You’ve mistaken my kindness for weakness,” Howard says, standing over him. “I’d like to think that tonight made a difference.”

Any boxer would. Howard is wrong, unfortunately, although the fight shows that he is the tougher man and the better strategist, as sharp and definitive in the ring as he is in court. Howard outboxes Jimmy but cannot defeat him in life. Howard does not realize that Kim is the brains behind the plot to ruin his career, a scheme that is to her—like everything else, it seems—a joke. Howard’s is a pyrrhic victory.

Nonetheless, Howard’s decision to box Jimmy shows physical prowess, a side of the CEO barely hinted at otherwise, by his sports car, for example. His decision to box shows that he is formal and intentional. He plans a refereed match with Jimmy, a fight, which means violence, sweat, perhaps even blood, but not a brawl.

The show’s writers establish stereotypes that apparently encompass the legal world, with attractive, neat, stylish Howard on one side and shaggy, windy Jimmy on the other. The boxing match transposes their competition into a form that usually leads to a clear result: the better boxer also seems to be the better man. That stereotype proves to be unreliable.

I thought of the stereotypes defining Howard and Jimmy when I saw this headline in the New York Times: “She Boxes. She Conducts. She Defies Stereotypes” (Javier C. Hernández, Times, The Arts, 2024/03/05). What stereotypes are these, and how reliable? The article concerns Elim Chan, a conductor born in Hong Kong and educated in the United States. I had just seen her conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and wondered what she had to do with boxing.

Better Call Saul defines stereotypes. The Times claims that Chan “defies” stereotypes associated with classical musicians. She told the Times that she is not what players expect in a conductor and that she has been “dismissed,” not because she is female but because she is petite and looks young. Players think that she is “too short or fresh-faced to be on the podium,” she says. Some ask, “Can we make the podium taller?” Others, “Is she 9 years old?” She is 37, and when the downbeat comes, they realize that she knows the score.

Chan is unorthodox. She maintains “an active life outside music” and “has become a devoted boxer, working with a coach between engagements.” She took up boxing a decade ago, when she moved to London, the Times says. She was looking for a way to prevent back and shoulder pain, and also searching for a way to clear her mind. Boxing filled the bills. She reports that she practices several times a week. “When I'm boxing I can't think of anything else,” she told the Times, “or I would get a black eye. And I love that.”

Chan works out as a boxer but, understandably, does not seem to get into boxing matches. We would not expect her to show up before elite audiences with a black eye or a significant bruise, marks that would not be understood as the result of boxing. Other audiences, however, would get a different message.

Chan won an important conducting competition in England ten years ago. A graduate student at the time, she was the first woman to win the prize. Her career was launched. About her victory, she said, “I do not want to be given any special treatment because I am a woman,” and added, “I do not want my gender, my femininity, to become a crutch of my own.” Boxing supports her desire to avoid being stereotyped as female, girlish, and petite.

It was clear in Chicago that the younger members of the audience saw her as one who defies expectations, as a trailblazer. When she strode on stage, in a dress with lace sleeves and a long, full skirt (but in flats, not heels), they greeted her as if she were, what else, a rock star. In my 40 years at Orchestra Hall (Symphony Center), this kind of raucous cheering is a recent development. It comes mostly from the upper tiers of the house. Enthusiasm on the main floor is hearty, but more restrained. Most of us had never heard of her, but her social media followers had clearly spread the word.

Looking at Chan’s schedule, I would guess that workouts with her boxing coach are not frequent. Presumably her coach is in London. In May 2024 her schedule included Chicago, Minneapolis, Seattle, Amsterdam, and Antwerp. Perhaps she will visit her London base in June and get in some rounds between her performance in Antwerp and her upcoming visits to Dresden and Berlin.

When she was in New York in March, Chan spoke at Smith College. A Smith alumna, she talked to young women who were thinking about careers in the arts, telling them that, in her view, it is becoming more difficult for women to have careers in conducting. Her interview with the Times does not explain why this is the case, since everywhere now one sees women developing careers in areas once dominated by men.

If the "pressure is insane," as Chan told the Times, that is because there are now many women in the conducting business. At the CSO recently we have seen Marin Alsop, Lina González-Granados, Susanna Mälkki, Dalia Stasevska, Lidiya Yankovskaya, and Xian Zhang, not to mention Chan herself. Ten years ago, women conductors were rare. That is no longer true. Conductors who talk about boxing, however, will continue to be a novelty.

What does boxing do for Chan?

Chan boxes for upper-body exercise. Nothing works the arms and back muscles better than boxing does. Nothing is better for the brain, either, than the intense concentration that boxing, including boxing workouts, requires.

Boxing is precise; punches have names and numbers. In order to do high-speed drills with your coach, you have to learn combinations of three of four or even ten punches, tightly sequenced. Everybody knows “jab, cross,” meaning your lead hand, usually your left, and your power hand, for most people, the right. There are four punches besides jab and cross: left and right hooks (elbow at 90 degrees, arm across the chin) and left and right uppers (again, elbow at 90 degrees).

The right hook

The left upper. Illustrations by Ed Igoe from Jack Dempsey, Championship Boxing (Simon and Schuster, 1950)

There are whole how-to-box books about combos, Dempsey’s being one of the best. Combos are the heart of boxing conditioning. When you work out with your coach, he will position his mitts to catch your shots. You better land them in the right place. He might call the shots in different combinations, and at some point footwork will figure into it, with pivots coming between some shots. When you get good at this stage, the coach no longer call shots but will position his mitts and test your speed in getting your glove to the right spot. That part of a good boxing workout approximates sparring.

For me boxing is a constant battle between accuracy and speed. This is also a battle for musicians. They build up skills with their own versions of combos, such as scales and passage work (crossing hands, for example). In performance, nothing corresponds exactly to the countless technical exercises they have mastered. But without that mastery, they would not be able to perform. Likewise, in sparring, nothing corresponds exactly to the combinations you work on with your coach, but the muscles remember the separate moves and call them up on cue (ideally, anyway).

Before reading the Times piece, I assumed that nothing, short of a hanging, could concentrate the mind better than raising a baton before a hundred experienced musicians. Yet Chan says she puts on boxing gloves because she “loves” to be in a situation in which she can think of only one thing. I now realize that conductors have to think of many things all the time, many instruments, many markings in the score. They have to keep the big picture in mind as they manage hundreds of details. That’s a different kind of concentration.

Boxing simplifies and clarifies for Saul and Howard, men who are separated by social and ethical differences. We don’t expect a wealthy lawyer to take his grievances into the ring.

Nor do we expect orchestra conductors, male or female, to show up in the ring to practice their concentration. Boxing clarifies and simplifies for Chan as well.

Boxing clarifies something about her, as well as for her. She claims that she does not want her femininity to become a “crutch,” by which word I understand “excuse.” Boxing is never associated with femininity even when the boxers are women. By talking about what she gets out of boxing, Chan makes it clear that she is not frilly. She may be petite, but she wants us to know that she is powerful. She makes fun of frilly styles in her clothing choices.

When conducting, Chan has an elaborate plan to guide her. In a fight, however, she would do what all boxers have to do, which is to refocus from second to second. Compared to legal work, or performing a musical score, boxing and boxing workouts are stark and simple. Instead of an elaborate plan that plays out over dozens of pages and lasts ten or twenty minutes, or an hour or more, the boxer’s strategy is evolving every second. A strategy can become futile if your opponent moves the instant you try put it in place.

The context in which Howard boxes is different from Chan’s context, of course. Howard finds that power demonstrated in a boxing match cannot resolve a complex competition. Boxing does more for Chan. Talking about boxing sets her apart from her competitors. I have not seen her social media (she is not a Substacker), but her website makes no reference to boxing. So I don’t know what, apart from her relative youth and her sex, signals her distinctive qualities for her followers. Do the orange highlights in her hair help?

One way to appreciate the significance of boxing in “Black and Blue” and the sport’s place in Chan’s life is to consider the inverse of their decisions. Imagine a boxer closing a multi-million dollar real estate transaction under the scrutiny of bank presidents and CEOs. Or imagine a boxer leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the second symphony of Brahms. I can’t.

I find it plausible that a powerful lawyer might learn to box, and that an orchestra conductor would work out with a boxing coach. That’s because boxing is accessible to high achievers in white-collar fields. Boxing offers something to petite women and bookish men, and it is part of the genius of the sport that some of them feel they can give it a go. Boxing simplifies the competition that most professions submerge in ritual and layers of privilege. That’s why it’s a relief for white-collar professionals to box.

Boxing cannot express the content of conducting or music or law or oral debate. It is far from a mindless sport, but its expressive potential is like the expressive potential of dance—a dance, however, in which points are earned by hitting your opponent, and not in a symbolic way.

For white-collar professionals, boxing is a step up, a chance to demonstrate unexpected skills as well as bravado. You might think that for boxers law or music might be also be step up. I think otherwise. Audiences for boxing are much larger than those for classical music, say nothing of the courtroom. Top boxers earn a great deal of money, more for a fight, win or lose, than some lawyers and conductors earn in a lifetime. Boxing matches take place in spaces that seat 20,000 or more; in former ages, matches in outdoor settings could draw five times that many people. Classical concerts do not (popular music is a different thing).

Boxers who want to conduct Beethoven would have to learn a lot more than conductors have to learn in order to box, and, like Howard, confront an opponent in the ring. It is easier to train muscles than it is to acquire and store technical information in the brain. Nobody thinks otherwise. If I ever meet a boxer who wants to conduct Brahms, I will write about him. Boxing potential is something many people carry around in them. Conducting potential and lawyering potential are harder to find.

Those careers are not accessible to those who box. That said, what careers in music and law offer top boxers does not amount to much. Elite audiences are mildly impressed to find that Chan has some boxing experience, but, after all, any sport still enhances women’s aura more than that sport will enhance men’s. Boxing audiences would not be impressed to hear that a top boxer conducted an orchestra. Everybody has seen a boxing match in a film or on TV, if not in life. Boxing registers. Not everybody has seen the CSO perform Mozart, or knows who Mozart was. Mozart does not register, say nothing of Sibelius or Ives.

Elite professionals know that, at some level, they are incomplete, missing something. Boxing fills them out. Boxers might be wearing blinkers, but those I know do not feel incomplete. In fact, they see others as incomplete. They want to be better at what they are good at, not to take a shot at something they are not trained to do. Boxers want to box. They love to box, and for them that’s enough.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to George Paterson for reminding me of the boxing scene in Better Call Saul and for finding the interview with Chan in the Times. “She Boxes. She Conducts. She Defies Stereotypes,” Javier C. Hernández, The New York Times (2024/03/05) [The Arts/Cultural Desk].

Fascinating. The contrast between the two. I must confess I was totally enamored with Chan and her manner. I was curious enough to watch a couple of short youtube videos of her conducting and she did not disappoint. https://youtu.be/Mt8sDAA_qJc?si=uYMLOP3Pz9R-YjnH She is wonderfully graceful in her conducting. Makes me want to see her box!

Thanks Allen for another element of boxing that is rarely seen!

Intriguing piece here, Allen. I would probably call it "gentrified" or "lululemonised" boxing. But nevertheless, you point out how the sport can confer its best qualities even without the intent of becoming a "real" or "genuine" boxer.