Boxing books, boxing, and masculinity

Introducing new posts on book about boxing, boxers, and manhood

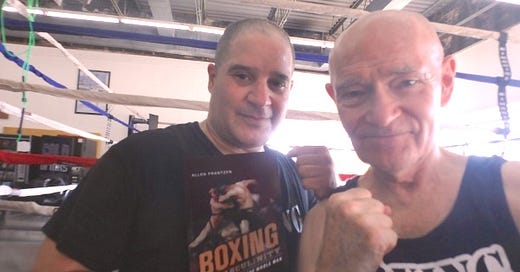

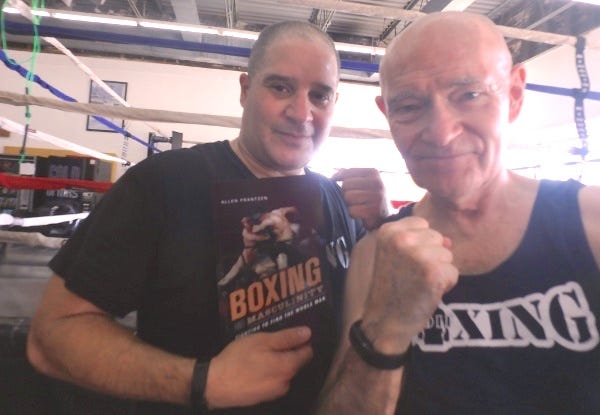

Boxing books aren’t just about boxing. They are also about manhood, a point I make in Boxing and Masculinity: Fighting to Find the Whole Man (at Amazon, in print and as ebook).

I have been interested in books all my life. When I was ready to retire, I got interested in boxing. Having never played any sport, or taken an interest in athletics, I expected to be out of my element in a boxing gym, both because of age (63 at the time) and because of my lack of experience. I was. I had taught and written about English medieval culture for nearly 40 years. My other interests were music, opera especially; cooking; and gardening, which was my only non-sedentary hobby. My interest in fitness began with therapy that followed rotator cuff surgery (an injury not related to exercise). I found therapy slow and boring. Hoping for a better experience, I hired a personal trainer.

There were no boxers at the trainer’s gym, but I did see some boxing gear. My curiosity grew when I saw a busboy in a restaurant throwing punches and shadowboxing around his buddy. The boxer had the word “Crusader” tattooed down one of his muscled-up arms. Along with grace and power, he radiated warrior confidence and manly exuberance. I wanted what he had. A week later I was done with my trainer and started boxing.

My boxing coaches were interested in strength, agility, and experience, not in books, degrees, or professional status. Wanting to learn more about what matters to boxers and their coaches, I turned to boxing books. They were more than stories about celebrated boxers. Many of them described how a boxer’s awareness of himself as a man affected the way he boxed. Boxing tested some men’s masculinity—Floyd Patterson’s, for example. Other men’s masculinity tested boxing, as with Roberto Duran and Muhammad Ali. I will be writing about manhood as it is treated in books about these and other fighters.

I support the long-standing belief that fighting is basic to male identity. In Boxing and Masculinity: Fighting to Find the Whole Man (2022, print and ebook), I explain why boxing is good for men of all ages, why it has been good for me, and why it would be good for you. I take up related ideas in Modern Masculinity: A Guide for Men (2016, ebook; both books at Amazon).

Today men’s inclination to fight is dismissed by progressives as a flaw. Society, however, has always exploited the fighting side of masculinity and continues to do so. Men are trained to protect others, not to protect themselves (Warren Farrell’s point). Men are required to register for the draft; women are not. Feminists are perfectly fine with this form of sex discrimination. If they were not, they would long-since have demanded that the law be rewritten to include women, and they would have gotten their way. Society denounces violence when it is virtuous to do so. But when war breaks out, society forces men to take one for the team.

It is an easy step from virtuous contempt for violence to virtuous contempt for boxing. Boxing is not only violent, sweaty, and often bloody, but also deeply traditional. That is why many people on the left look down on the sport as immature, mindless violence. They see it as a mix of in-your-face aggression and physical strength that is used to get the other guy before he gets you.

Leaving out physical strength, however, we see that this characterization of boxing also describes the left: mindlessly violent, as we saw in the riots of 2020 and the feeble excuses made for them; immature, as we see in the left’s preference for cancel culture over calm debate; and bullying, as we know from the hostility and abuse with which the left shames and attacks the opposition. Progressives are fine with violence, immaturity, and bullying, so long as it is their own brand of violence, immaturity, and bullying. They own up to these qualities under other names, such as resistance, vulnerability, and disruption. These people don’t like boxing, but they worship conflict.

Boxers earn their glory. Even in humble gyms, boxing elevates the male warrior and makes for magnificent masculine theater. The boxer has no club, no ball, no racket, no gun, no equipment but his gloves. Win or lose, he puts his art and strength on the line. Standing above the spectators, the boxer commands attention. You might walk past a tennis game or two golfers on the green, but you do not walk past two men in a fight.

Others have written about sports and masculinity, from both traditional and progressive points of view. I will tracing a shift from older studies by Eric Anderson, Elliot J. Gorn, and E. Anthony Rotundo to arguments about manhood and boxing from those on the left.